ELECTORAL AESTHETICS

I remember some of 1996. That election year nearly a quarter century ago is the subject and title of a new collection of essays—a time capsule, even—edited by artist Matt Keegan with interviews edited by writer and oral historian Svetlana Kitto. In 1996, I was either fifteen or sixteen years old, and I lived in New York City, where I took a bus or the subway to high school most days. I wore a lot of polyester clothes sourced from bins and bulging racks downtown. I carried a plastic wallet with cartoon frogs on it and lugged my textbooks around in a leather Village Tannery backpack that was way too small for the purpose and therefore had a weapon-like density. I read Hermann Hesse, Toni Morrison, Anaïs Nin, Gertrude Stein. I had never heard of David Foster Wallace, author of 1996’s Infinite Jest. I was obsessed with platform shoes.

I still don’t know where the determination to look and dress the way I looked and dressed in 1996 came from. It was, however, of such importance to me to wear the clothes I wore, and to use a specific eyeliner (white) and hair dye (blue-black), that over time I’ve wanted to decode this affinity. Since I thought less about the provenance of my thrift-shop finds than their colors and shapes, I have to believe I was after an image rather than a series of historical references—but what image was this, precisely? The decadence of the American nineties was a decadence of false minimalism, of up-cycling and appropriation, and of the dissimulation of enormous wealth and geopolitical power in textiles and imagery as “soft” as fake monkey fur or the underfed body of Kate Moss.

I couldn’t vote in 1996, and to the extent I remember that year’s election, it is for the pen that the seventy-three-year-old Republican nominee Bob Dole always clenched in his war-crippled right hand to mask its limited mobility. This, along with the candidate’s susceptibility to memory lapses, was subtly exploited by the Clinton-Gore ticket. Most of what I recall from 1996, if this can be said to be a politics, has to do with messages related to sex. In spite of the country’s having emerged from the puritanical Reagan-Bush years with Democratic triumph in 1992, sex, we were told, was unsafe for a number of reasons (shame, pregnancy, infection). I did not think of this as a sign of the times or evidence that the liberalism of the executive was frequently merely symbolic—saxophone stylings covering for continued dismantling of the social safety net and high rates of incarceration. Instead of thinking such things, I got up each morning and arrayed myself as if I were a visitor to the present from some other, possibly fictional era.

Keegan writes in his introduction that the election of 2016 was an intellectually and politically transformative moment for him, motivating him to investigate “changes that the Democratic Party went through in the run-up to Bill Clinton’s emergence as a presidential candidate in 1992.” The essays, interviews, archival images, magazine and newspaper clippings, and shots of art installations he and Kitto collect in 1996 focus on the experiences and points of view of artists who were either in or nearing their twenties in 1996, some voting for the first time in that year’s election (including Becca Albee, Thomas Eggerer, Malik Gaines, Chitra Ganesh, Pearl C. Hsiung, Jennifer Moon, Seth Price, Alexando Segade, Elisabeth Subrin, Martine Syms, and Lincoln Tobier, among others). The anthology also features contributions from a number of other disciplines, exploring the 1994 Crime Bill and the 1996 Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act meant to reduce welfare; the AIDS crisis; racism and carceral politics during the 1990s; poet Eileen Myles’s 1992 presidential campaign; American immigration policy; Israel, Palestine, and American foreign policy in the Middle East; and the climate crisis, among other touchstones, many of which significantly affect the present or remain with us in hardly altered forms. The book includes essays by such writers and scholars as José Esteban Muñoz (“Pedro Zamora’s Real World of Counterpublicity: Performing an Ethics of the Self”), Yigal S. Nizri (“5756, Jerusalem”), and Mychal Denzel Smith (“A Lesson to Be Learned: On Clinton’s Approval of the 1994 Crime Bill and the 1996 Welfare Reform Act”). The book’s guiding animus is the notorious movement toward business interests and globalization effected by the Democratic Party in the platform of William Jefferson Clinton, (in)famously evidenced by the 1994 implementation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), a Reagan initiative that was finally stewarded into existence by the forty-third chief executive. Keegan explains the relevance of his research to our present situation: “I would argue that this rightward move [of the Democratic party] is also foundational to Joe Biden becoming the Democratic presidential nominee in 2020.”

Keegan has a point. As rhetoric in the lead-up to this month’s contest has tended to emphasize the anti-democratic statements and policies of the incumbent, as well as the GOP’s more general affinity for low turnout, restrictions on voting, creative districting, and indirect representation, 1996 reminds the reader of a longer history of norms, messages, exclusions, and coalitions—Republican, Democratic, and otherwise. One of the most interesting things about the writings and pictures the book assembles is that, although a great deal of this material originates in the year 1996, much of it does not. A number of essays are set several years before or a decade or so after the titular year, suggesting that even as we have a tendency to corral events into discrete dates and spans of time, our experience of them can be far more amorphous and ambiguous. In particular, essays by journalists Ahmad Ibsais and Jordan G. Teicher on global warming and the denial thereof show the ways in which political rhetoric and the news have wreaked havoc on our sense of time and causality. As Teicher notes in his concise history of climate-related misinformation from 1996 to the present, 1996 has the alarming distinction of being the last “cool” year in human history, with its average of 51.88 degrees Fahrenheit just shy of the twentieth century’s overall average of 52.02. “Every year since,” Teicher writes, “it’s been hotter.”

The anthology deploys ephemera very effectively, handily shocking the reader with the stupidity of mainstream ideology of the mid-1990s. A 1996 Kenneth Cole ad, touting the brand’s next-level wingtips, proclaims: “The year is 2020. Computers can cook, all sex is safe and it’s illegal to bear arms and bare feet. The future is what you make it.” Such items—along with an image of Ivanka Trump as teen model or a fear-mongering depiction of the pledge of allegiance in Spanish and German from the xenophobic nonprofit “U.S. English,” still operational today—provide some of the strongest tastes of the moment and foreshadow its lingering social and political effects.

The 1990s were the heyday of so-called scatter art. Although scatter art has perhaps not held up as well as other late-breaking takes on conceptualism (like those of Felix Gonzalez-Torres), some of its interest in the power of metonymy and everyday artifacts has clearly been absorbed—not uncritically—into 1996’s modus operandi. Interspersed among the essays are images of pieces dated 1996 by Rachel Harrison, Roni Horn, Glenn Ligon, Cady Noland, Jack Pierson, Lari Pittman, Julia Scher, Wolfgang Tillmans, Kara Walker, Nari Ward, and Andrea Zittel, along with a still from 1995’s CREMASTER 1 video by Matthew Barney—all of which appear without comment. However, there are no photographs of works by such artists as Mike Kelly, Karen Kilimnik, or Paul McCarthy, who are often understood as dominant artists of the time, and these omissions felt purposeful as well as refreshing. I did, however, sometimes wish that 1996 leaned a bit harder on Keegan and many contributors’ area of expertise, i.e., visual art. It might have been nice to include at least one essay surveying the ubiquitous installation-based work of the 1990s or discussing the numerous artworks illustrated, particularly as the collection is well positioned to explore 1996’s art in an original way, given its wide-ranging interest in policy and popular visual culture. That the book’s ambition to focus on a rightward shift in American liberalism is not more fully explored via “high” art, as opposed to mass media, seems like something of a missed opportunity; or, perhaps the reader is simply meant to connect the dots. Yet, while juxtaposition can be a powerful aesthetic tool, it tends to produce suggestive resonances rather than clear argument, and the reader of 1996 might have benefited from a bit more lucidity with respect to the role of artworks in this historical moment. Given that Rudolph Giuliani serves as Trump’s lawyer today, the book might have considered, for example, his failed attempt to censor Chris Ofili’s 1996 glitter-and-elephant-dung-adorned painting The Holy Virgin Mary while it was displayed at the Brooklyn Museum in 1999. Although Giuliani was widely hailed as a hero for his actions around the World Trade Center’s collapse shortly thereafter, his authoritarianism and disregard for the First Amendment had already been made clear when he sued and attempted to withdraw municipal funding from the Brooklyn Museum. It is interesting to consider how the art of 1996 might, for the perceptive reader, have decrypted the neoliberal politics of the time—de-normalizing them, as it were—even before these politics became more legible in hindsight.

Two of my favorite pieces in 1996 manage a difficult feat where nonfiction is concerned: that of being at once historically informative and intensely personal, showing how we may experience major historical changes as they are unfolding in the present. Debbie Nathan’s essay recounts her time as the Texas chair of Eileen Myles’s 1992 write-in presidential bid. As Nathan notes, Texas has gone Republican in every presidential race since the 1980s. Nathan, who would otherwise have voted Democrat, decided, after attending a poetry reading by Myles, “that if I was going to throw away the coin of my vote, I might as well toss it into a wishing well of hope.” She joined Myles’s campaign (its slogan: “Veto the mainstream! Stay outside! Vote for Eileen Myles”). She quickly discovered that she was too late to submit signatures necessary to get Myles on the ballot. Undeterred by this or her friends’ dismay at her enthusiasm for an independent candidate, Nathan, a journalist and immigrants’ rights advocate, joined the poet-candidate to paint a giant WRITE IN MYLES on a concrete embankment of the Rio Grande in El Paso. But this is only the beginning of Nathan’s account. She details the Democrats’ ramping up of policing after Clinton’s first success: a 1993 op-ed in the Los Angeles Times by Democratic California senator Dianne Feinstein calling for tougher measures on immigration, as well as Biden’s 1994 Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, signed by Bernie Sanders, among others. By the time 1996 rolled around, Clinton’s position on immigration was hardly distinct from that of his Republican opponent.

Michael Bullock’s “Cruising Diary: 1991–2001,” meanwhile, is a memoir of navigating the early internet’s male-seeking-male offerings. Bullock recounts his teenaged attempts at cruising and use of a telephone chat line advertised in a newspaper (the source of one very creepy encounter), bringing the reader along as he begins to experiment with web-based communications and, in the process, to reckon with desire, risk, and safer sex. In 1996 there were only limited and somewhat awkward options via real-time chat rooms, but by the early 2000s Craiglist’s personals section had blossomed. Encounters with one Craigslist poster, “ZebraShades,” demonstrate to Bullock the power of the anonymous message board to facilitate new kinds of connection, along with the fulfillment of very particular erotic needs. As he writes, “Digital space allowed a generation of men to grow together, enabling us to each fearlessly seek out our own ZebraShades.”

The verb “to normalize” has become a favorite shorthand in the present, yet 1996 calls our attention to a much longer series of successful and politically devastating normalizations, which we would do well not to ignore or forget. It is a kind of art to establish familiarity and normalcy where, in truth, none can or should inhere. In this sense, as we know, artists are far from the only ones who are creative in their jobs; marketers and political strategists are creative, too. The Jamaican-American artist Dave McKenzie, writing in a new essay on his 2004 performance We Shall Overcome, makes the following observation:

I know the internet and social media supposedly explain Trump, but weirdly enough—and this is why I think of him as the television president—I wonder about there being some sort of delay. At some point, we’ll have a YouTube star who’s president, but maybe not for another fifty years or something. But I’m wondering how each Clinton—from Clinton to Clinton—each moment or figure exposes something in the very recent past of media, of culture. They’re dragging with them some idea from the generation just prior.

If McKenzie is correct, we should be thinking about 1996 today because it is this moment’s media ecosystem and its political events that are likely to affect if not determine the present. I’m not sure what it might mean to be governed by a YouTube president, to extend McKenzie’s metaphor, but it does seem clear that four more years of “the television president” would be an instance of the past not merely influencing the present but overwhelming and, in some sense, displacing it. Overall, 1996 is an informative and, in the end, hopeful collection, demonstrating that we can learn a great deal from recent history, even as the time remaining to apply these urgent lessons grows increasingly short.

On site.

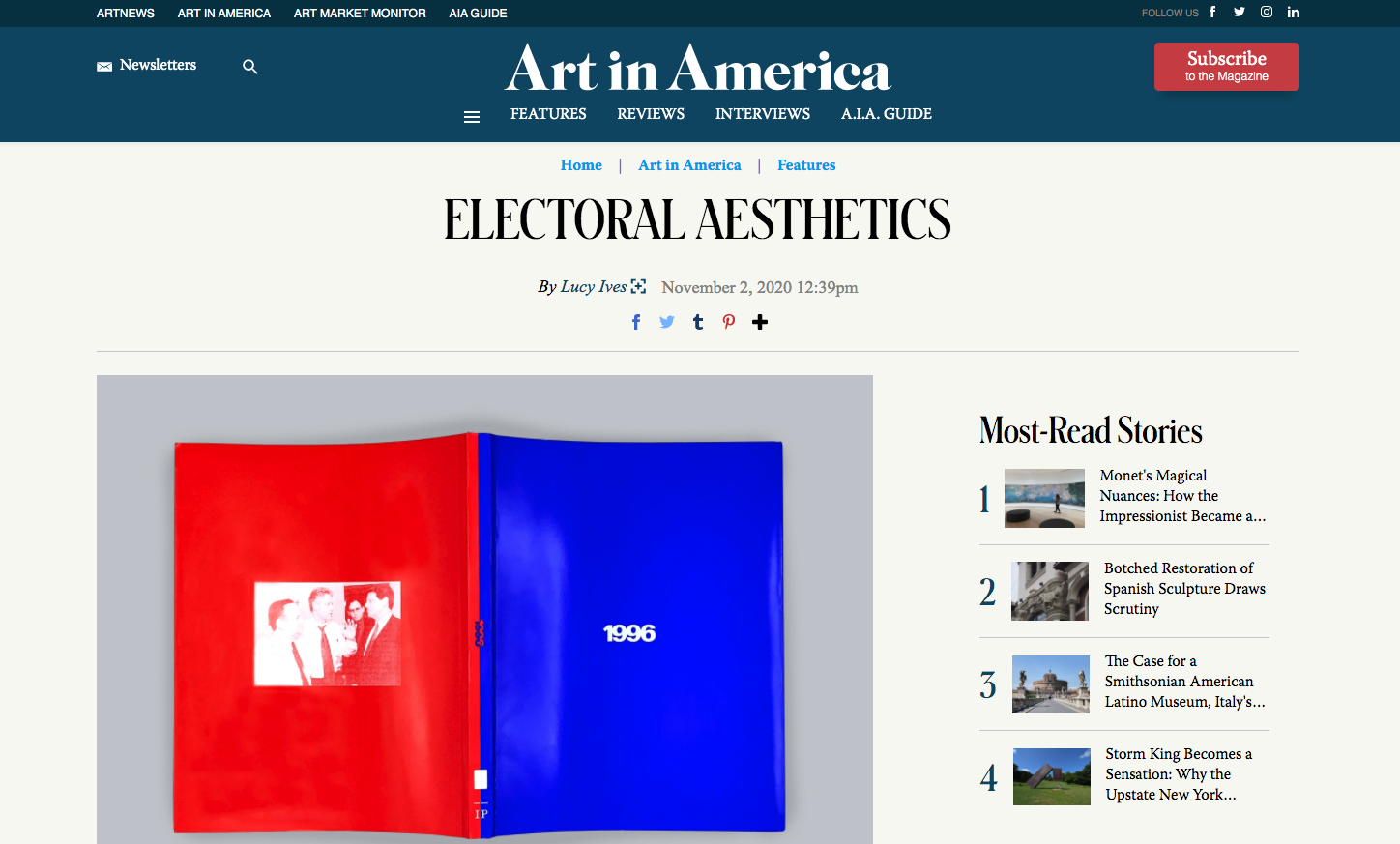

Matt Keegan's book 1996, with interviews edited by Svetlana Kitto, Inventory Press.