FOR THE REVERSAL OF UP AND DOWN

Would you know how to look at the Antarctic, if you were lucky enough to travel there someday? What would you expect to see? Probably you, like me, anticipate a frigid landscape of snow and ice (endless ice), dotted with penguins at its coasts. We may well imagine the North Pole—that non-place taxed by its incorporation into the modern consumer rite called Christmas—doubling it, attaching it to the other side of the globe, a twin, striped post opposite or upside down, as it were. Of course, whether you and I are aware of this, language has already invited us into this fantasy of symmetry: we are thinking of the anti-arctic, that which is opposite “the bear,” i.e., Ursa Major, the prominent constellation of the northern celestial sphere; we are thinking, too, thus, of the arctic, from the Greek arktos, “bear” and, via the magic of metonymy, “north,” from which the more familiar Latin ursus comes. But would we know how to look at the Arctic, either? I vaguely remember (likely this is apocryphal) a moment from grade school, right before a geography test, someone hissing, “Which is the one with bears, again?”

I know few people who have been to the North Pole—not a spot on land, we will recall. Fewer still have been to Antarctica—the one with land, no bears. When I was 23, I traveled by train between Sweden and Finland, stopping overnight in Kiruna, a Swedish town north of the Arctic Circle and home to one of the deepest iron ore mines in the world. It was July and remained light out seemingly at all hours. With some advance arrangement, a tourist could pay to travel down into the mine, but I am afraid of heights and had no wish to do this. A year later, I learned that the local government had decided to relocate the town.[1] Human intervention had irrevocably altered the state of the ground; Kiruna had begun to sink. As of 2020, the movement of buildings and persons two miles to the east of Kiruna’s former inner city is ongoing and will continue for another two decades. In May of this year, the largest seismic event ever caused by mining, a 4.9 magnitude earthquake, was reported at the Kiruna mine of Swedish company LKAB. The scale and risks of this now more-than-a-century-old project, along with the sums of money involved, are dizzying, staggering, disorienting. Which way is up? I think. According to Wikipedia, in 2012 the depth of the mine attained some 4,478 feet, which is to say, around the height of many peaks in the North American White Mountains, some of which I can perceive from a window in the room where I am currently sitting, typing.[2] I also think, losing my bearings for a moment: Am I above or am I below?

The artist Himali Singh Soin has created a lens and a language for seeing in such states—which may also be landscapes—of disorientation, where up and down cease to be opposed and commonplace direction founders. Her ongoing project, we are opposite like that, which is comprised of videos, an artist’s book, as well as a musical composition and performance, partly documents travel she undertook to uninhabited parts of the Arctic’s Svalbard archipelago and the Antarctic Peninsula. It is additionally a reading of the fantastically disoriented and disorienting way of regarding these parts of the world that grew up during the so-called ages of polar exploration, the periods of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries when European men set off in boats and heavy woolen clothes, hoping to access frozen reaches where they would prove their autonomy and valor by planting flags in shimmering patches of snow and ice, which were then to belong to the nations from which they came. They went in quest of efficient global circulation, pursuing a Northwest Passage, also engaging in the industrial harvesting of ice—a project that may seem quite strange to us, given contemporary refrigeration technology.

Significantly, as Soin shows in her most recent video, produced in 2019, those who remained at home were not immune to the spectral lure of these otherworldly realms, where hallucinations, disappearances, and cannibalism on the part of Europeans who sought to stake a claim or find a passage were not unknown. A negative fantasy arose in Victorian England alongside scientific research into prehistoric glaciers: when the world ended, it would end in ice. As if persecuted at long range by the very recalcitrant icescape that had consumed Captain Sir John Franklin’s mission of 1845 to discover a Northwest Passage, Victorians pictured themselves as threatened interglacial beings in popular prints and culture. They imagined the ice appearing at their doors, polar bears menacing them on the weekends at their parks, their cities enveloped by a genocidal crystalline substance. In one 1868 print by caricaturist Gustave Doré, featured in Soin’s video, a “southern savage,” who is somehow unaffected by the collapse of civilization so-called, gazes out at an empty London whose inhabitants have not survived a freeze or other apocalyptic catastrophe.

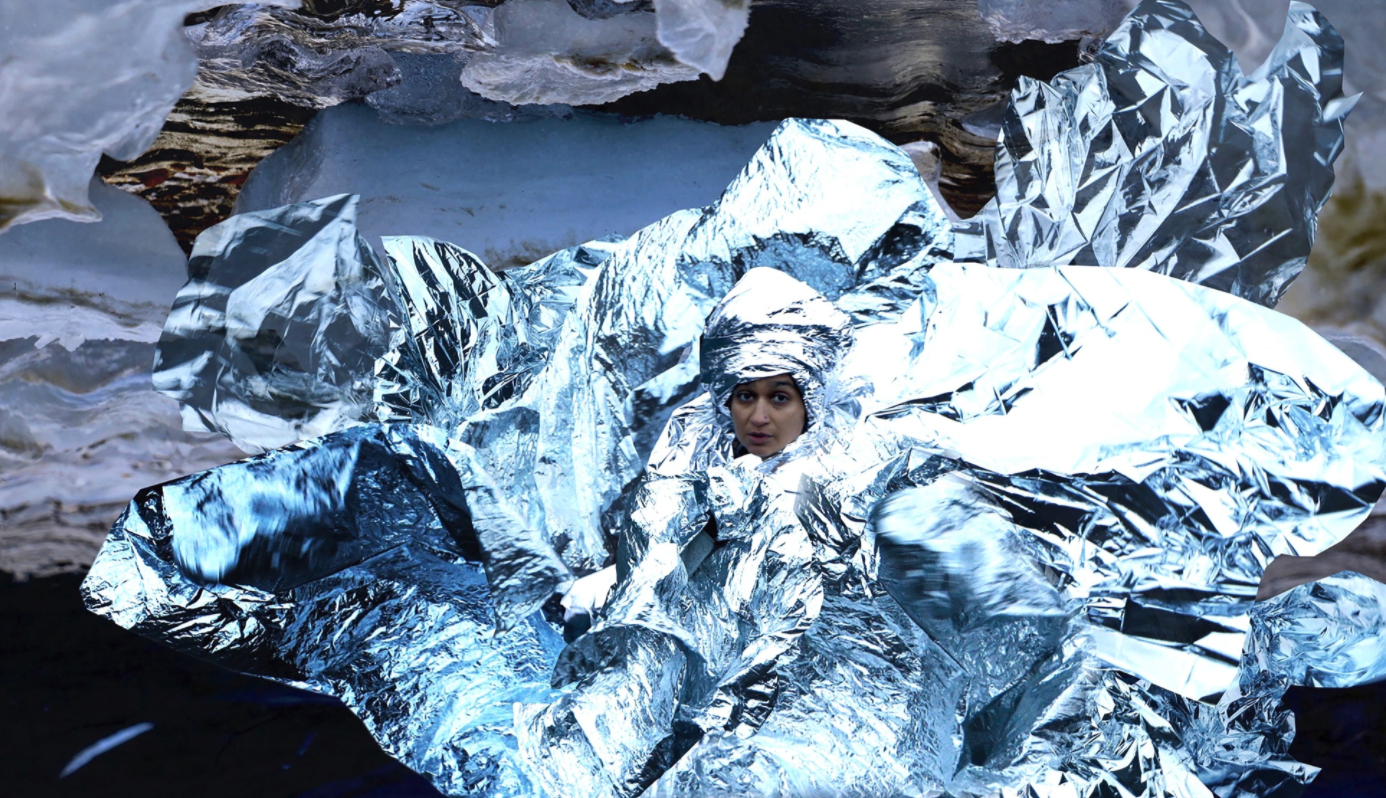

At the center of Soin’s work is a figure portrayed by the artist herself. Dressed—and sometimes seeming to nest—in a cloud of silver emergency heat blankets, this being emerges from frozen masses or walks slowly across tundra, her reflective garments shimmering and loosening in the wind. She is ice, personified. She is still here. Her movements, focused gaze, and undulating attire act as stand-ins for what the art historian Maggie Cao, an expert in landscape painting of the nineteenth century, has termed ice’s “ever-present liquidity,” its liability to “fracturing, restructuring, and, of course, melting,” its “material contradictions.”[3] We watch as ice, solid and slow and never not in motion, departs. Soin’s figure also harbors contradictions of political history: for the Victorian sailor or imperial captain ice was at once a living adversary and cherished lifeless property; ice was a place where nothing was, into which one was compelled to travel; it was a void to be filled, a glamorous screen, a phantasmagoria at once colorless and containing every imaginable color; a killer of and magnet for fantasies; nothing and too many things. It was feminine, other. We need, it seems, some way of looking at ice. We need a language—possibly multiple languages—to address her. We are already too late.

In 1895, the year of the earliest confirmed European landing on Antarctica by the Norwegian steamship Antarctic, a Swedish physicist named Svante Arrhenius was devising the first mathematical model of what we now call global warming, showing by 1896 that increased CO2 levels in the atmosphere could lead to dramatic heating of the planet. In spite of the appetite for coal in his industrializing time, Arrhenius was unalarmed and viewed his discovery as predictive of a relatively slow process of climate change, by way of which it would take thirty centuries for CO2 levels to grow by 50 percent, his marker for a planetary temperature uptick of five to six degrees Celsius. As we know, it has in fact taken a single century for CO2 levels to increase by 30 percent.[4]

In an email, Soin tells me, “When I finally traveled to both antipodes, they weren’t spaces, but places of loss that needed to quickly be written in order to be preserved in some way.” This sentence produces a vicarious immediacy for me: I realize that I cannot go to the North Pole, even if I do someday and somehow travel to the point in the Northern Hemisphere where, to employ the technical definition, the Earth’s axis of rotation meets its surface. Who knows how I might get there but, beyond this, who knows what sort of solidity I would be likely to encounter, what will remain of the ice in this place predicted to be passable by ship within the coming decade?

Thus I turn to the canvas-bound book that accompanies Soin’s video, hoping to orient myself in time and space via writing (a long habit with me). The book is also titled we are opposite like that, and it is taller along its spine than it is long across its pages, giving it the air and heft of a log book of some sort, a portable item that might fit in a large pocket.[5] I think, speaking of writing and pockets, of the titular coat fabricated by Herman Melville’s narrator in his 1850 novel, White-Jacket; or, The World in a Man-of-War. This allegorical outer garment is a palimpsest, reinforced with whatever fabric comes to hand in an urgent situation aboard a ship headed for Cape Horn, “bedarned and bequilted” by the wearer “with many odds and ends of patches—old socks, old trowser-legs, and the like.”[6] The jacket is a bound object, a sort of book with pages gathered from various sources but lacking writing: like the pale whale set to appear in Melville’s subsequent novel, the jacket is blank. It has, unfortunately for its wearer, not been waterproofed with tar—a foreshadowing of challenges to come—but, and moreover, its whiteness bespeaks the uncertainty and radical ignorance of the young sailor, who may himself be inscribed by events at sea. In book form, Soin’s we are opposite like that is also a palimpsest, but it overflows with writing from many sources and in varied genres and styles, from calligraphic poem to brief play to chart to litany to history. In one extraordinary essay, Soin makes an argument for thinking of the aurora as “a form of art writing,” for example; elsewhere, she provides a guide that may be used to “FOUND YOUR OWN LANGUAGE.” “Bequilted” into the center of the book, which may be read beginning from either cover, is a rectangular fragment cut from an emergency blanket.[7] A reader familiar with Soin’s video might, coming to this silver page, have the sense of brushing the hem of ice’s raiment. The character, if not ice, is abruptly, materially present.

Maggie Cao advises us to read the history of ice as “reveal[ing] the intersection of environmental and political imperialisms that have long fueled our dreams and fears of entropy.”[8] I think about this history as a force for reorientation; for replacing, rescaling the grid, much like the crossing, telescoping, turning lines I read in Soin’s book. I am learning some ways to look and read. I am learning that my own disorientation has language in it—for opposites, like hallucinations and distortions, come with, and from, language. And disorientation, like any language, must have a history.

*

The title of this essay borrows from that of a 2006 artwork by Tavares Strachan, Chamber with Ice: Elevator for the Reversal of Up and Down, an installation including ice harvested from Alaska, a refrigeration unit, solar panels, fans, flags, and a battery system, exhibited in Nassau, Bahamas. Strachan’s work is discussed in both of the essays by Maggie Cao I cite in the writing above.

Date: October 5, 2020

Publisher: Columbia University GSAPP Arthur Ross Architecture Gallery

Format: Web

Genre: Nonfiction

Link to the exhibition site.

This essay appears as a part of A Wildness Distant, an online screening room accessible during fall of 2020.

On site.

Himali Singh Soin, still from we are opposite like that (2019). Image courtesy the artist.

- The relocation of the city is the subject the exhibition Kiruna Forever, currently on view at ArkDes, the Swedish Centre for Architecture and Design in Stockholm.

- Maggie Cao, “Icescapes,” vol. 31, no. 2, American Art (Summer 2017): 48.

- Himali Singh Soin, we are opposite like that (n.p.: subcontinentment press, 2020).

- Herman Melville, White Jacket; or, the World on a Man-of-War (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1850), from Chapter 1, “The Jacket,” https://www.gutenberg.org/files/10712/10712-h/10712-h.htm#chap01.

- I use the metaphor of quilting loosely here, as the silver page is not in fact bound into the book but is held in place by static electricity and the weight of the other pages.

- Maggie Cao, “The Entropic History of Ice,” in Ecologies, Agents, Terrains, edited by Christopher P. Heuer and Rebecca Zorach (New Haven and London: The Clark Art Institute and Yale UP, 2018), 267.