RAYMOND ROUSSEL

Galerie Buchholz

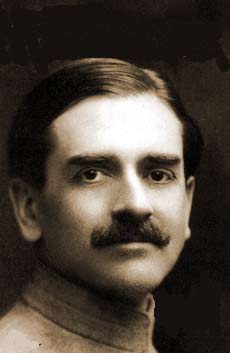

Difficult author; reclusive aesthete; visionary fabricator of fantastic objects literary, conceptual, and material: The reputation of Raymond Roussel (1877–1933) often precedes him. In photographs he is a pale, impeccably groomed man with a resplendent moustache. A shy smile pairs oddly with the wild energy in his gaze. His writings, allegedly incomprehensible to all but the most committed appreciators of his day still receive less attention than his biography or, what is perhaps more accurate, legend.

Galerie Buchholz’s recent exhibition is the latest view into the Roussel annals. It also functions as a housewarming: Previously exclusively a Berlin concern, Buchholz now has a foothold near the steps of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Behind the robust façade of a townhouse of the sort normally occupied by foreign embassies, Buchholz’s three-room offering of Rousseliana is an extremely welcome addition to the neighborhood and feels, more generally, like a happy return to a fan favorite. Roussel’s work never gets old—partly because of how strange it is, and partly because so few people have actually read it.

Roussel wrote long, formally and conceptually complex poems, as well as novels. He is best known for 1910’s Impressions of Africa, a novel that he published at his own expense and later mounted as an elaborately costumed play. The structure of the novel is famously based on the punning difference between two otherwise identical, seemingly insignificant phrases: les lettres du blanc sur les bandes du vieux billard (white letters on the cushions of the old billiard table) and les lettres du blanc sur les bandes du vieux pillard (letters of a white man about the bands of the old pillager). Beginning with the first of these two arbitrary images, Roussel concludes 26 chapters later with the second; in the pages between, he describes the court of an imaginary African king at which, in a fantasy of colonialism reversed, a troupe of European entertainers are detained, forced to enact various impossible tableaux.

Like the prose of Marcel Proust, Roussel’s oeuvre marks the encounter of Victorian representational styles and ideas about time with those that come to characterize modernism. Unlike the prose of Marcel Proust, Roussel’s writings are not concerned with phenomenal reality. Instead, Roussel wants his readers to consider unreal visions already mediated by writing or other technologies, not experiences but rather images of experience; Roussel is a practitioner of the trope of ekphrasis, or description of another work of art in writing, par excellence. In Impressions of Africa, in what amounts to a displacement of lived time by performances and scientific experiments, unusual devices give rise to new images and texts. There are light-projecting plants; a glass-enclosed mechanical orchestra powered by the thermal sensitivity of bexium, an imaginary metal; a photo-mechanical painting machine. These “machines correspondantes,” as Gilles Deleuze called them, have the additional effect of rendering ornament essential rather than “removable,” as in Walter Pater’s formulation. For Pater—whose stylistic economy was influential for modernists from Proust to Ezra Pound—the “surplusage” of decorative language diminishes meaning. Pater’s rules are passionately flouted by Roussel, whose nearly nonsensical ekphrastic delays, or stoppages, produce exciting excursions into speculative artistic and scientific practice.

Galerie Buchholz helpfully parses Roussel’s relationship to Proust by means of the inclusion of two editions of Proust’s prose-poem collection, Les Plaisirs et les jours, published in 1896, the year before the appearance of Roussel’s first novel-in-verse, La Doublure. This juxtaposition is characteristic of what is most exciting about the show’s display of numerous books, which allows us to draw our own conclusions about the milieu in which one might have encountered these publications for the first time. Even more startling and immediate are enlargements of a series of Roussel family snapshots, some taken by Raymond, including a close-up of Madame Roussel and a pet dog with eyes that appear to be made of glass. Here we glimpse a largely unknown corner of the archive.

Yet far more space in this modest gallery is devoted to the better-known reception history: Roussel’s influence on artists from Marcel Duchamp (who attended a performance of Impressions of Africa) to Joseph Cornell to Marcel Broodthaers; the connection to Surrealism; the American poet John Ashbery’s oft-cited importation of Roussel’s work into American English; Michel Foucault’s early monograph. Such diverse adulation for the show’s subject is reassuring, but upon coming to the fourth vitrine stocked with untouchable publications, one begins to wonder what, in the age of worldcat.org, when bibliographies of obscure texts can be instantly formulated, one is looking at. The sheer quantity of materials included in the show, along with recent works by Cameron Rowland and Henrik Olesen, among others, feels a bit like a missed opportunity. Though for Roussel more was always more, he always advanced via carefully designed procedures. More and more we want narrative and arrangement, space to think about the overwhelming amounts of information we receive; it might have been nice to consider the ways in which Roussel’s miraculous inventions anticipate our desire.

Date: November 1, 2015

Publisher: Artforum

Format: Print

Genre: Nonfiction

Link to the essay.

Full text of review available as PDF, below at right.

November 2015 AF cover.

R.R.