MONUMENTAL INVISIBILITY

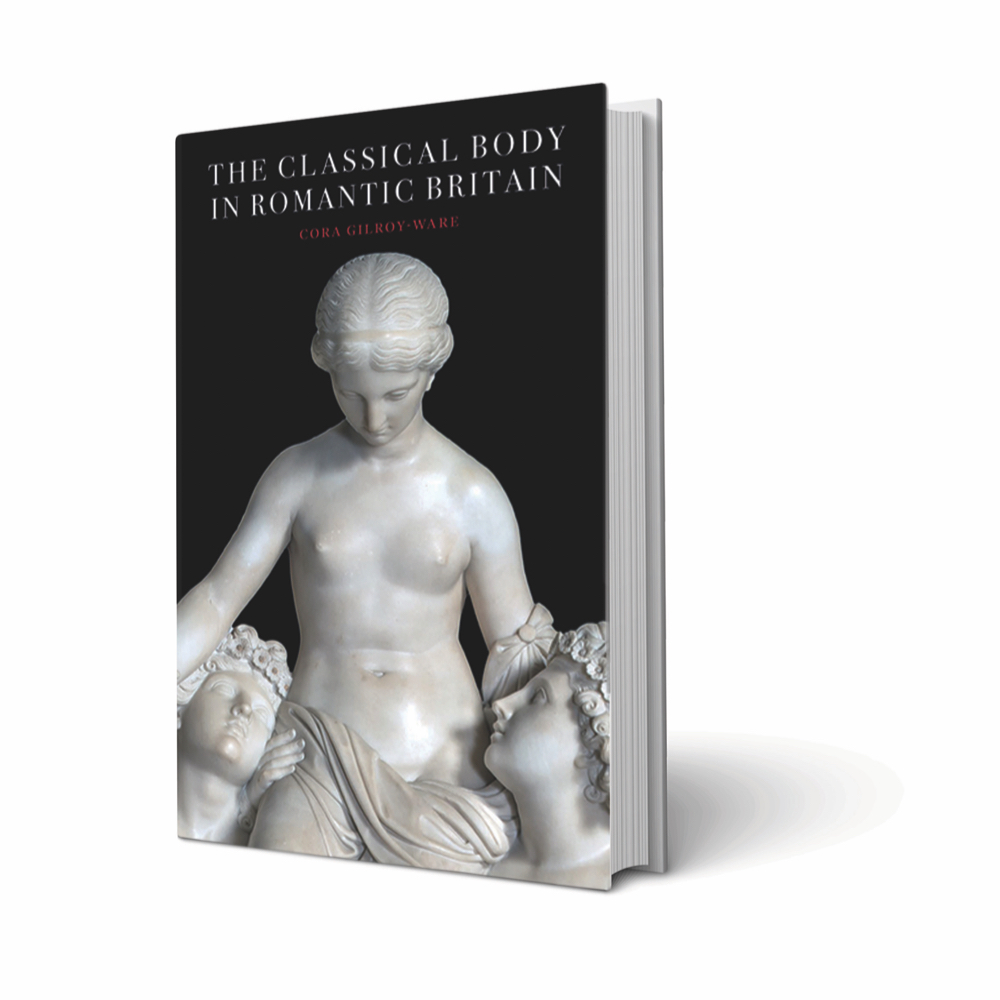

Review: The Classical Body in Romantic Britain

Cora Gilroy-Ware’s engaging study of nineteenth-century Neo-Classical sculpture, The Classical Body in Romantic Britain, brings an invigorating new interpretation to a style that many contemporary viewers too often see as either dull or self-congratulatory. A visitor to St. Paul’s Cathedral in London who passes the large marble war monument depicting Captain Richard Rundle Burges may be perplexed to find that this naval captain, who lost his life in 1797 during the Battle of Camperdown, is all but nude. Draped in what appears to be a wrinkled tablecloth, Burges accepts a sizable sword from an attending winged Victory. It is perhaps no wonder that, as Gilroy-Ware points out, the 2012 Rough Guide to London calls this statue “overblown” and questions its dorky sensuality. Figurative marble statuary from this period is indeed hard to look at: derivative of numerous earlier classicisms, it is often engaged in modes of historiography and/or moral allegory that bypass or clash with contemporary concerns and values, promoting sorts of idealism that seem outmoded when not openly celebratory of imperial violence, extractive economic practices, and white supremacy.

Gilroy-Ware’s triumph in The Classical Body is to carefully re-politicize what we perceive as the daffiness, essentialism, homogeneity, and what she terms the “Dream” or “Poem” of such plastic works—to permit us to see them again, reknit into the aesthetic and discursive context of their times. She additionally succeeds in drawing connections between the smooth surfaces of these objects and later expressions of Neo-Classicism, from the fluttering garments of modern ballet to the hard bodies of Nazi symbols to the hyper-depilated form of the Victoria’s Secret “Angel.” Her book is generously illustrated with full-page color images of statues, paintings, and graphic works, and it is fascinating to discover therein that what this writer, for one, took to be the cliché of the ubiquitous pale marble statue in the nineteenth century was in fact a complex means of working through an array of dispositions to public life as well as political and national sentiment. For example, Thomas Banks (1735–1805), creator of the seminude Captain Richard Rundle Burges, was a leftist activist, abolitionist, and pacifist, committed to an “egalitarian classicism.” Gilroy-Ware observes that for Banks, “the classical body became a vessel for utopian ideas.” Although Banks’s disposition was not widely shared, it is noteworthy that appropriation of so-called classical styles during this period did not always connote an enthusiasm, on the part of the artist, for endless imperial wars and colonialism.

The Classical Body’s central argument is that, in Britain, an engaged form of classicism, associated with radical republicanism and revolution, was gradually replaced by a saccharine, tacitly nationalist classicism as the nineteenth century wore on. Whereas France’s Neo-Classical nudes were tasked with allegorizing the power of the popular body released from the shackles of monarchy, British artists navigated a different set of concerns, more rarely expressing democratic values—or, for that matter, any direct political values at all—through their increasingly “Poetic” works. As Gilroy-Ware writes, “The definition of the classical body was especially sensitive to historicizing tendencies, . . . it readily lay open to revisions at any minute.” The British government’s purchase of the looted Parthenon Marbles from Thomas Bruce, Earl of Elgin, in 1816 is one significant example of the way in which Britain embraced an imperial—here, Athenian—classicism. Artists (such as the aforementioned Banks) for whom the nakedness and dynamism particular to Greek, Roman, and later Italian sculpture might serve as an “emblem” of physical liberty and self-determination, as well as the possibility of a more equal society, were succeeded by individuals more concerned with satisfying middle-brow appetites for cavorting nymphs and militaristic muscle-bound hunks.

Gilroy-Ware thus moves the reader from the early 1800s—sometimes thought to have been an era dominated by “Grand Tourism” and the aristocratic manipulation of Classical themes, but which she reads as a more complex and diverse period of assimilation of both past sculptural styles and the writings of eighteenth-century popularizers of ancient art such as Johann Joachim Winckelmann—into the second, third, and fourth decades of the century, when what she terms “Poetic sculpture” overwhelms the utopian “Dream” originally embraced by more radical artists. She discusses Banks’s antiwar figures (some of the most revelatory passages in the book), as well as the “draped Dream” of the toga-heavy royalist creations of sculptor John Bacon Sr. (1740–1799), the origination of a “sweet” style by the draftsman and sculptor John Flaxman (1755–1826), the sylph-filled paintings of Henry Howard (1769–1847), as well as the unrelentingly sugary marbles of celebrity-artist Antonio Canova (1757–1822), which she places into illuminating dialogue with the poetry of John Keats (1795–1821). A significant chapter, “Living Dreams and Poems,” considers the horrific treatment of Saartjie Baartman (1789–1815), forcibly exhibited in the 1810s as the “Hottentot Venus,” in relation to changing British mores and conventions of sculpture and display. A regressive culture no longer pursued an “active connection between Greece and Freedom” and saw no paradox in “putting a captured African woman on stage and calling her Venus.” In this chapter, Gilroy-Ware additionally details painter Benjamin Robert Haydon’s use of a Black sailor named Wilson as a model. Having studied and sketched Wilson’s body for a month in 1810, Haydon began a year later writing a series of pseudonymous pieces as “An English Student” for the Examiner, making aggressive pseudoscientific claims regarding white superiority and purported ancestral ties to ancient Greece, employing the Parthenon Marbles as a primary example of his “racial ideal.” Here, Gilroy-Ware demonstrates how the classical body was rapidly becoming a discursive object, enabling the ideology of slavery, “the false consciousness that allowed for the exploitation and exchange of human beings as if they were inanimate things,” to overtake and replace any remnants of egalitarian political sentiment.

I first came to Gilroy-Ware’s work via an essay she published in 2019 in X-TRA magazine, “Knowledge-Montage: Page 3, Poetic Sculpture, and Print.” I was immediately taken by her fluency in multiple registers of thought—melding precise art historical narrative with contemporary commentary (on cheesecake tabloid nudes, in this particular essay)—and her highly original style of affect-theory-influenced interpretation. She deployed these in such a way as to permit me to see the interconnections and resonances inherent to the various layers of her scholarship. I was additionally struck by the synthetic and even intermedial nature of Gilroy-Ware’s overall theory of “Poetic sculpture,” a type of derivative image-making that “ushers the viewer into a remote and disinterested space,” one that is pointedly free of accurate historical narrative and rather trades in sentiment and sensuality. Throughout Gilroy-Ware’s writing there is an exciting and, I think, productive tension: While she excels at capturing the material qualities of works of sculpture (“tender, feeding the desire to caress,” “lathered in a balm,” “finished to a lactic sheen”), her goal in The Classical Body in Romantic Britain is not in fact to detail surface particulars or related techniques but rather, as she writes, “to de-aestheticize objects by bringing to light their lost connection to politicized art.” That she comes to this de-aestheticization by way of the haptic and visual qualities of sculpture forces us to contend with the works in question both as historical objects and as objects located squarely, and often uncomfortably, in the present. In this sense, Gilroy-Ware writes against modernist novelist Robert Musil’s ironic contention, cited in The Classical Body, that “there is nothing in the world as invisible as monuments.” Gilroy-Ware re-substantiates appropriations of the Classical body along with related value systems; in other words, she renders visible that which she ably deconstructs.

Date: October 7, 2020

Publisher: Art in America

Format: Print, web

Genre: Nonfiction

Link to the essay.

This review appears in the print edition of Art in America, November–December 2020.

November–December 2020 cover.

John Gibson, Venus, 1862, marble with polychromy, Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool.

Cora Gilroy-Ware, The Classical Body in Romantic Britain, New Haven and London, Yale University Press, 2020; 320 pages, 109 color and black-and-white illustrations.