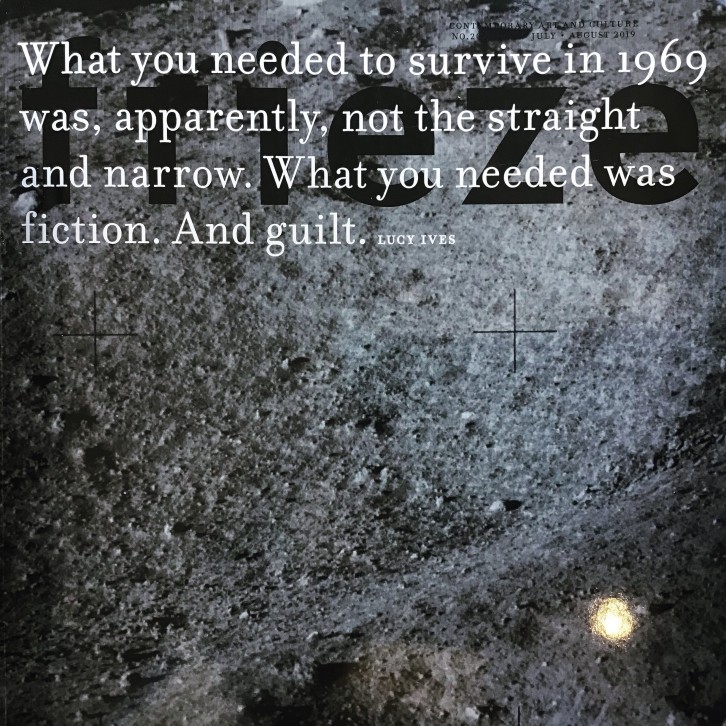

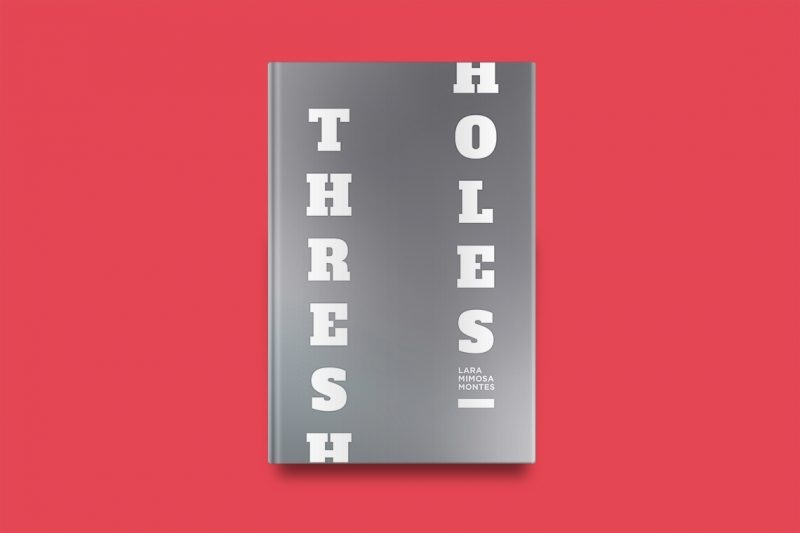

A THROW OF THE DICE

When we were first married, he went out and bought a ball gag. It wasn’t something I asked him to do. He wasn’t a tall man but I suppose he was reasonably strong. He had a construction job, at the time. It was the sort of work he claimed to prefer.

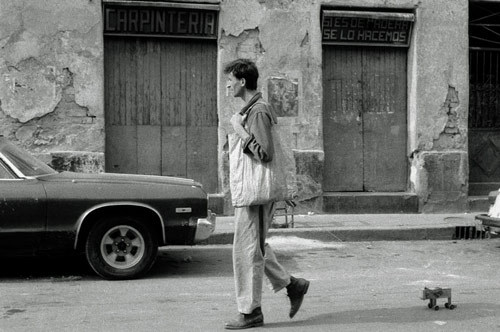

We were living in San Francisco and through some act of god managed to find an apartment we could afford in an occasionally fancy neighborhood. It was just two rooms with a kitchen, the bathroom memorable for its coordinating sink, tub, toilet, and floor-to-ceiling tile, all a click shy of Pepto-Bismol. Outside, in the mornings and at dusk, an oddly shaped vehicle I learned to call the Google Bus rolled darkly by.

He was up at five, cycling into the East Bay. Around seven, the garage door screwed into the ceiling that was also the floor beneath our bed (a mattress) went into action. It was a braying sound, accompanied by copious vibration. During this process, I envisioned what I believed to be the exact fashion in which the building would collapse during an earthquake. I saw myself mangled in rubble. I lay, intact within the intact building, in bed, possessed by vertigo.

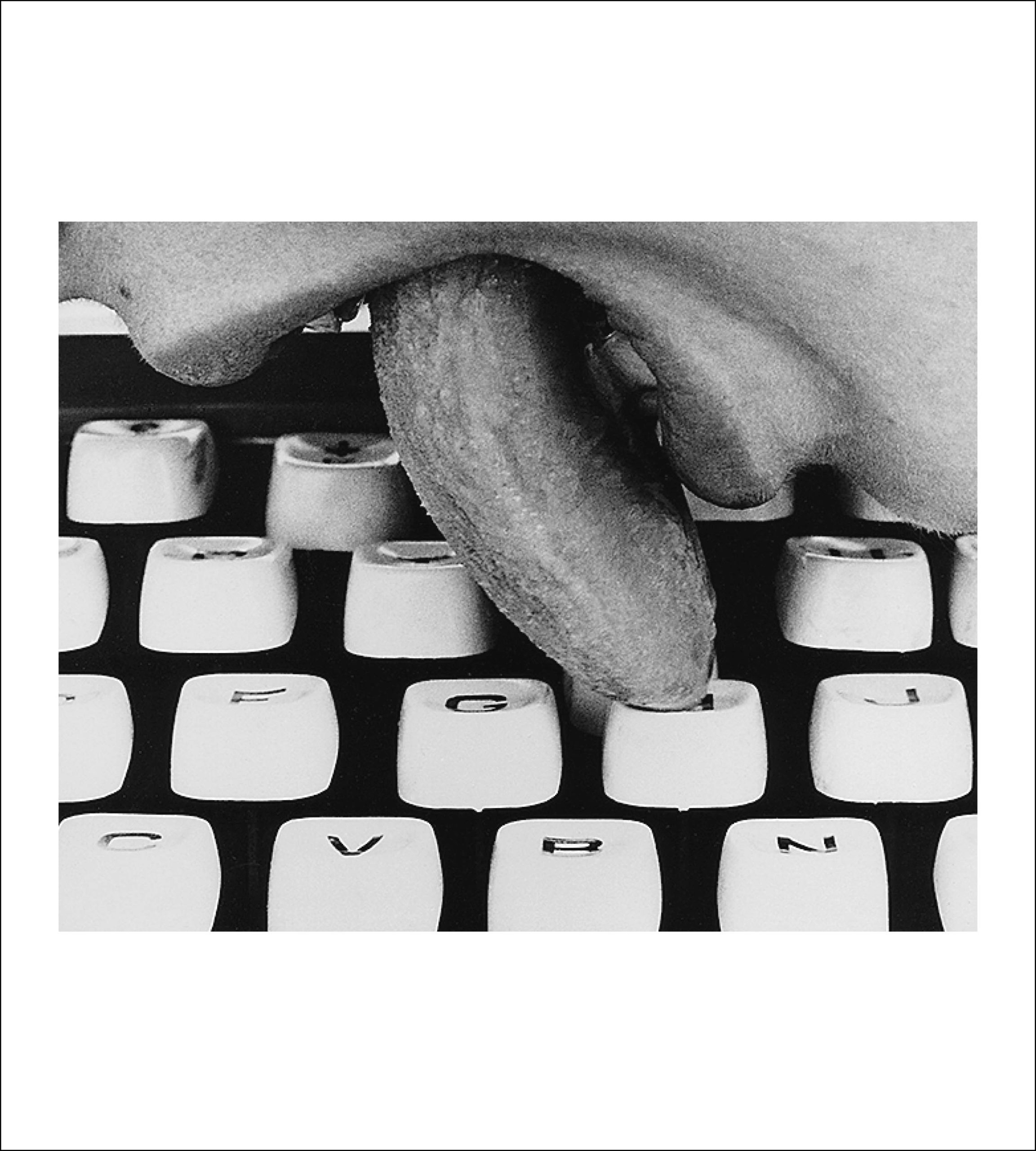

I did not work in tech, either. I worked fulltime for an employment agency. I had originally gone in to temp but had been hired as the front-desk girl. An Australian man with outrageous good looks, benefiting from the immigration policies of President George W. Bush, had hired me, citing my unusual abilities as a typist. Although I insisted that I preferred something with fewer hours, the agency maintained that it was low on contracts and could I please take them up on this offer, seeing as I was unlikely to receive another.

Yes, I said.

Great, they replied. Wonderful. “I am so pleased!” announced the Australian, glinting hugely. He really was astonishing, ranching in his family, eyes and teeth like polished rocks. He began telling a long, long story about his very young wife.

●

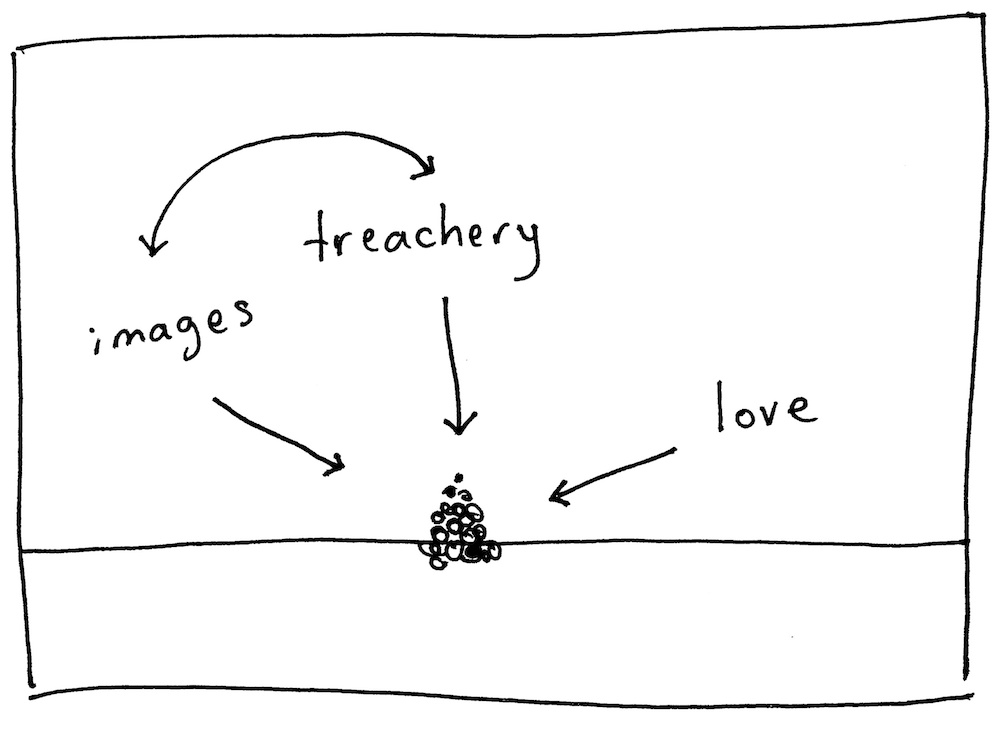

I thought all the time about how much I loved him. It would come to me as I was walking down the street. I loved him, the man I was married to and, as well as being afraid of earthquakes, feared that one of us might die in a plane crash or be pulled down by a rogue wave. I thought of meningitis, serial killers, war. Fog rolled up the hill. It was night again.

I cut up cilantro. We sat at our table by the window and had a beer.

He went on several shopping excursions. He returned with bags stuffed with violet tissue. He quietly reentered the house.

It was a Sunday.

He restrained me.

●

He was, as I was saying, not a large man. He was a relatively small man, and he was full of a searing rage, an odorless, colorless flame, unknowable to the naked eye. We’d take the bart to a party and pass card tables set up by proselytizing Scientologists, and he would explain that they believed all humans were animated by the souls of aliens long ago subject to genocide.

I wanted to take the stress test, but he wouldn’t let me. “L. Ron Hubbard was like, I’m going to invent a truly stupid religion. Look at these people,” he said. He seemed not to want to get too close to them, but I noticed a week later two novels by Philip K. Dick in his open backpack, The Man in the High Castle and The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch, Dick having allegedly inspired Hubbard to devise his intergalactic creed. There was something vaguely gothic about Dick, I thought, something sharp and in bad taste. He was paranoid yet flavorful, industrial strength.

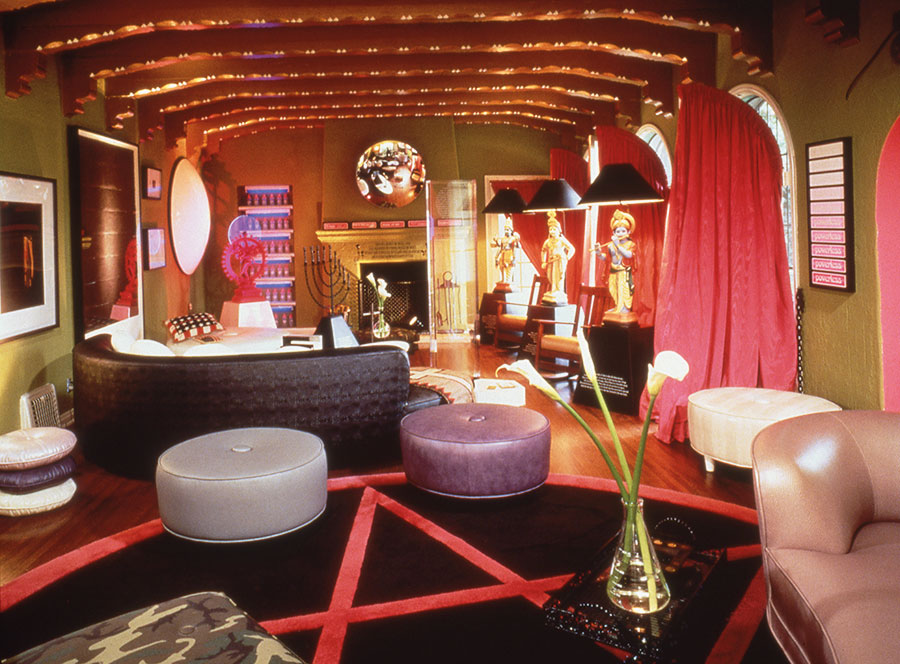

We had a friend who’d grown up Mormon but renounced the faith at seventeen and ran away from home. He’d lived in a basement in Oakland for a few years before going to college, then grad school. He had about twenty tattoos and a gold front tooth and loved antique furniture and cocaine. He and the man I was married to went through a period of binges, and somehow I associated it with Scientology. I’d listen to them discuss the unusual activities of the Angel Moroni and the irony of Abendsen’s The Grasshopper Lies Heavy, before we parted ways for the night, they to a fortress maintained by an eccentric dealer on Potrero Hill, I to my translations and, more importantly, Craigslist.

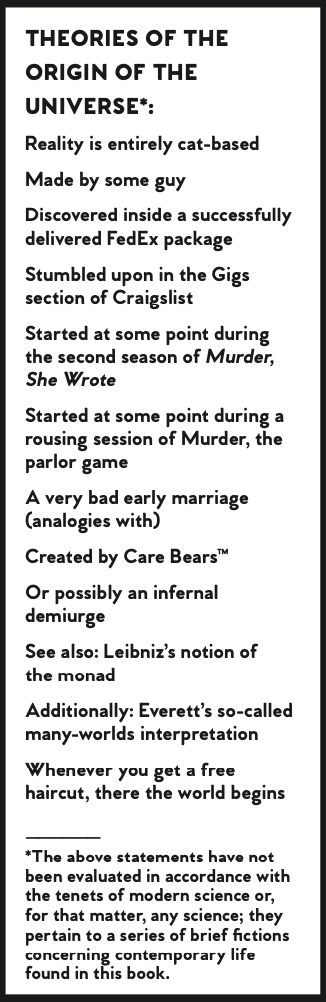

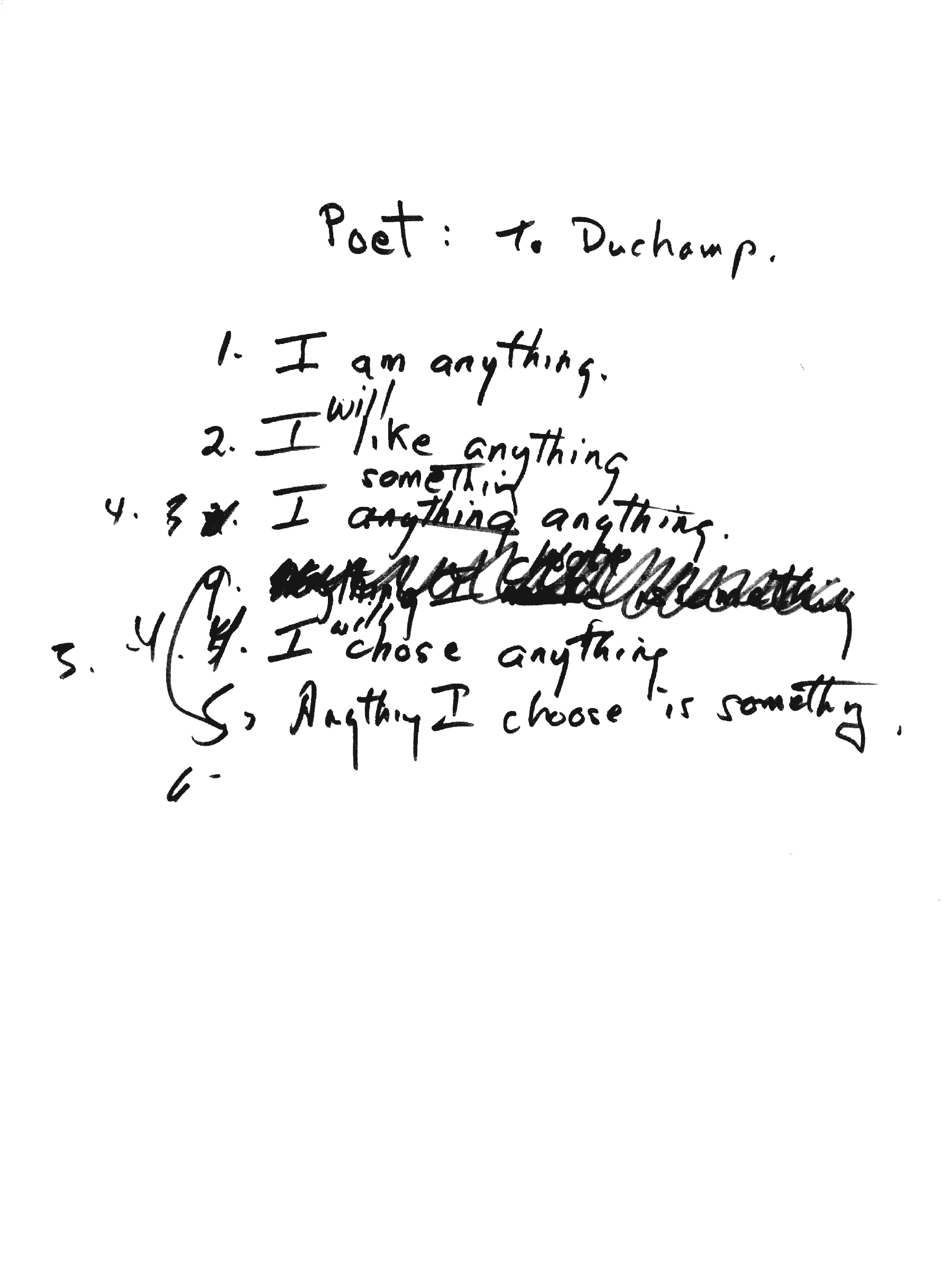

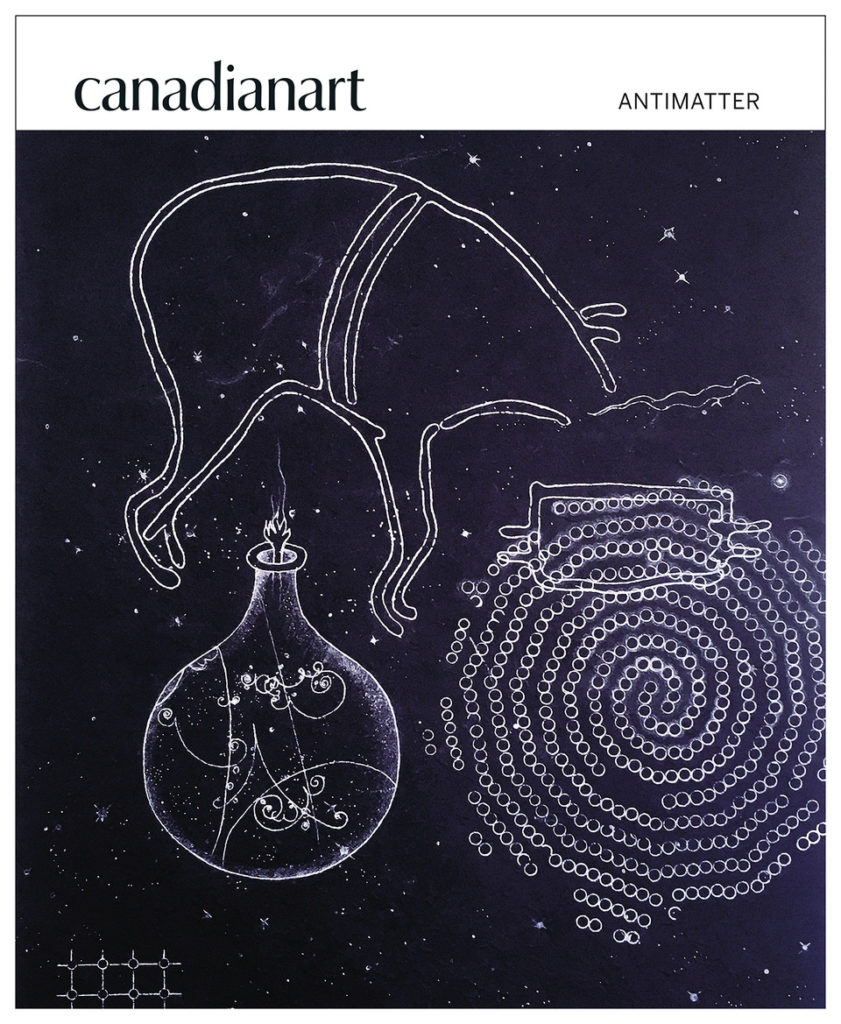

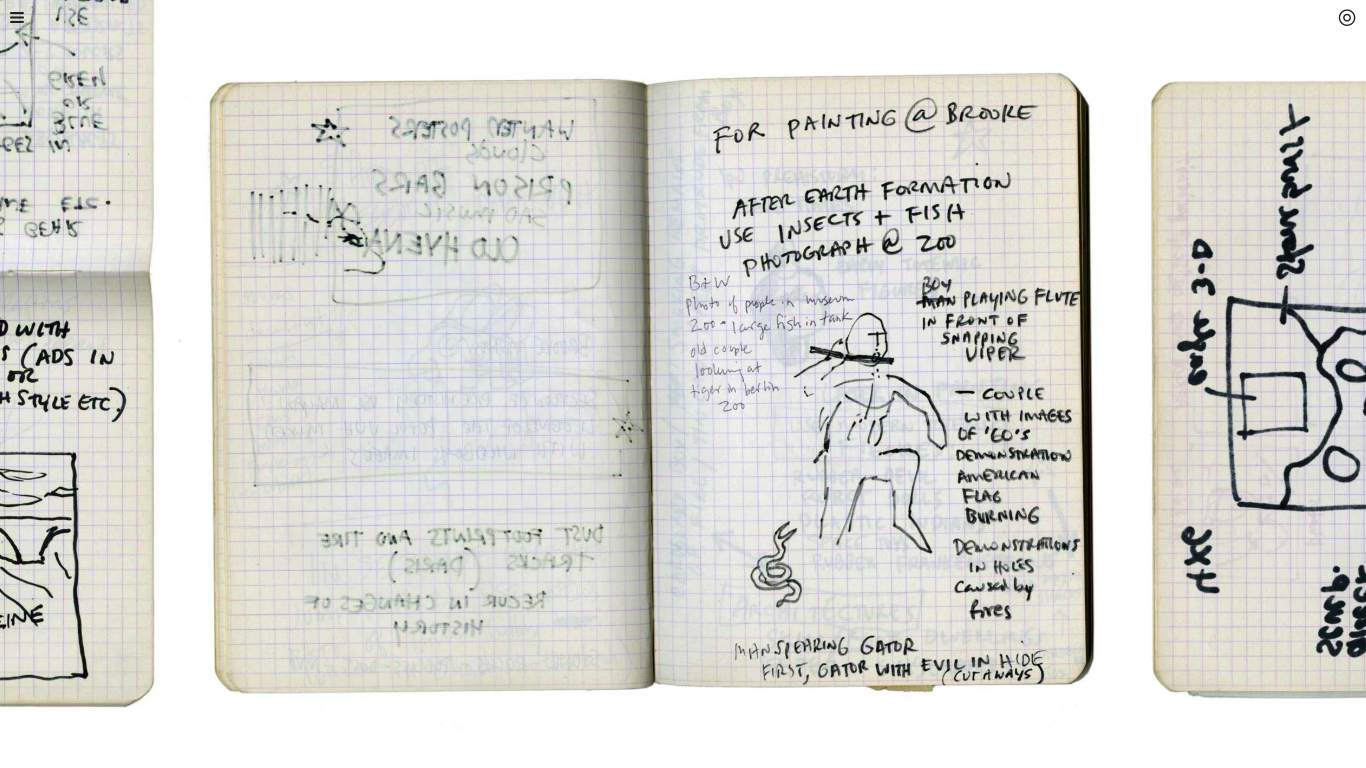

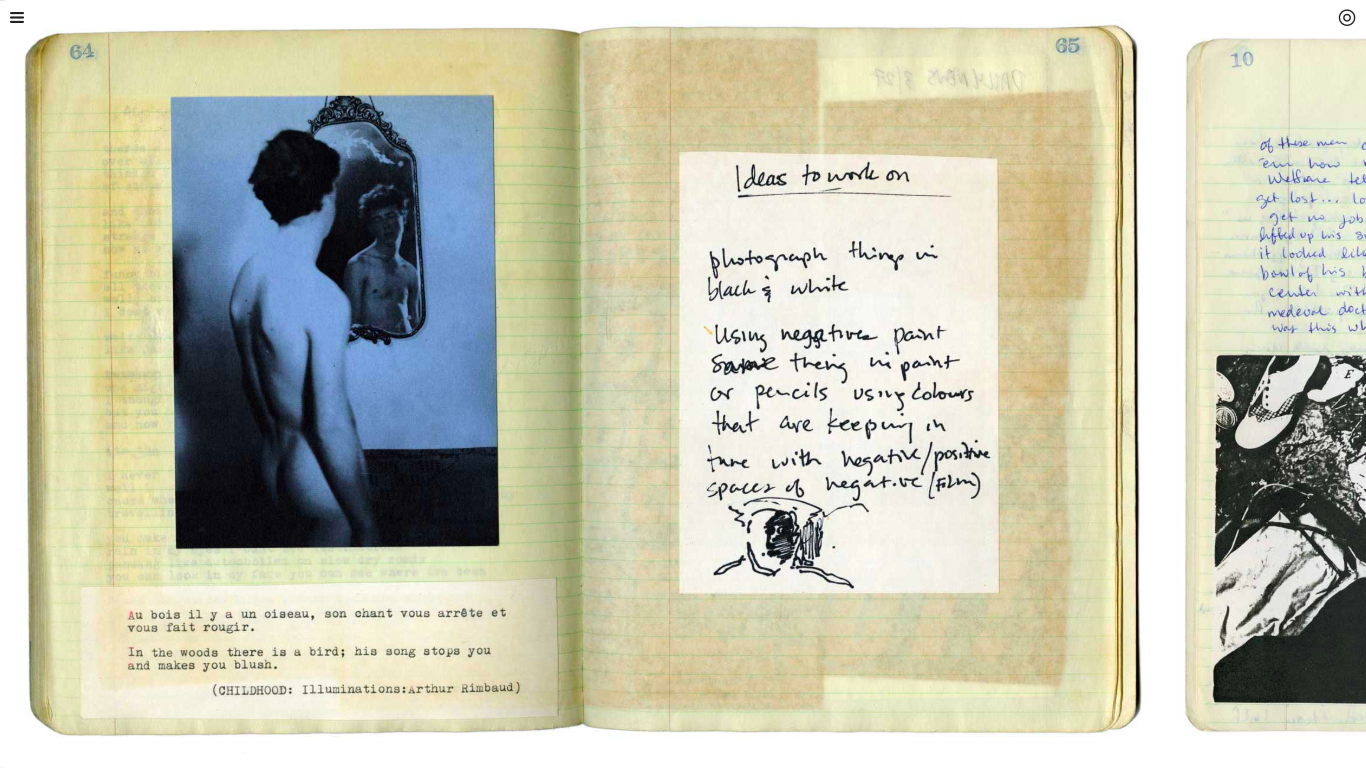

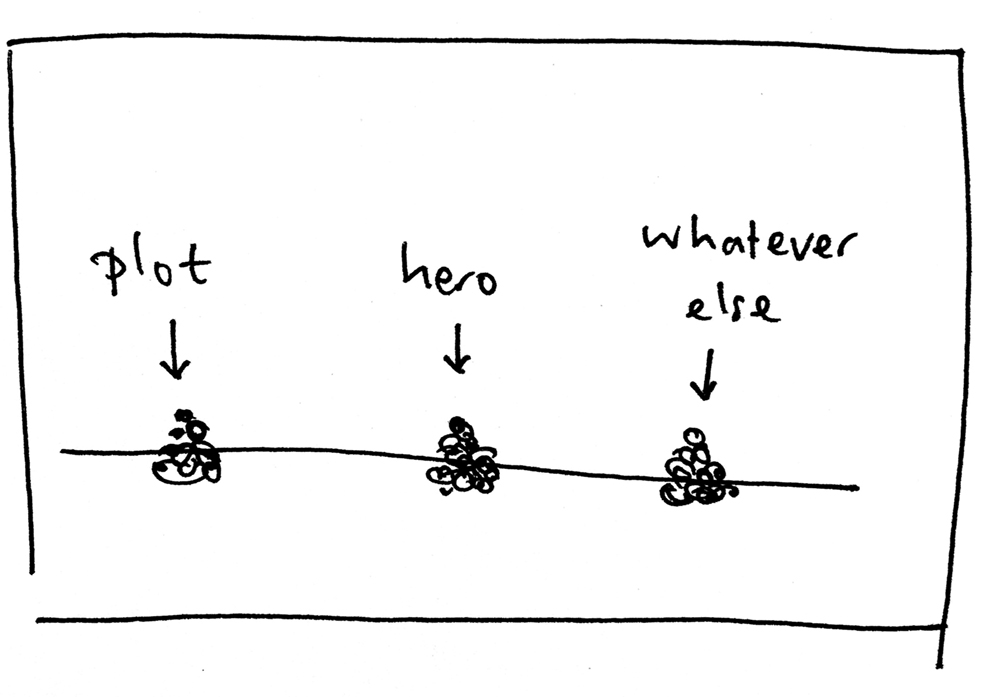

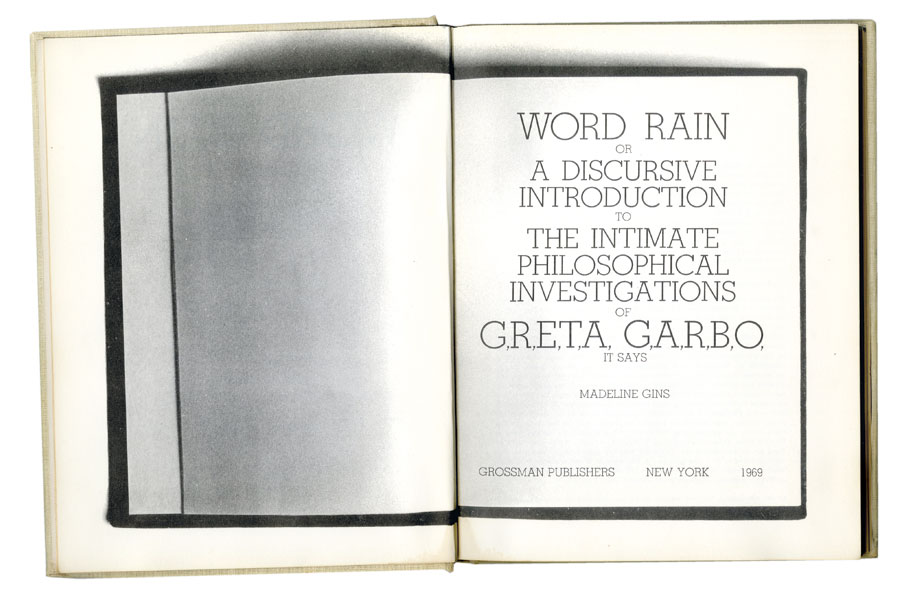

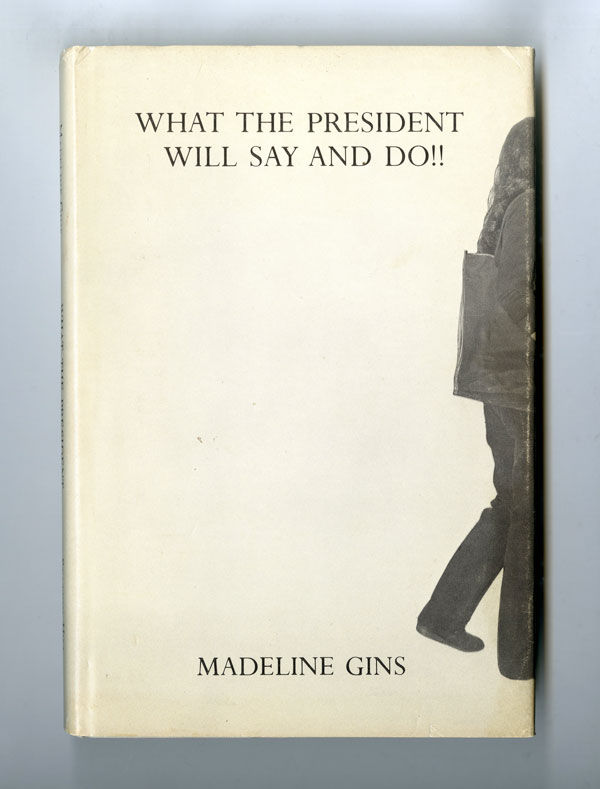

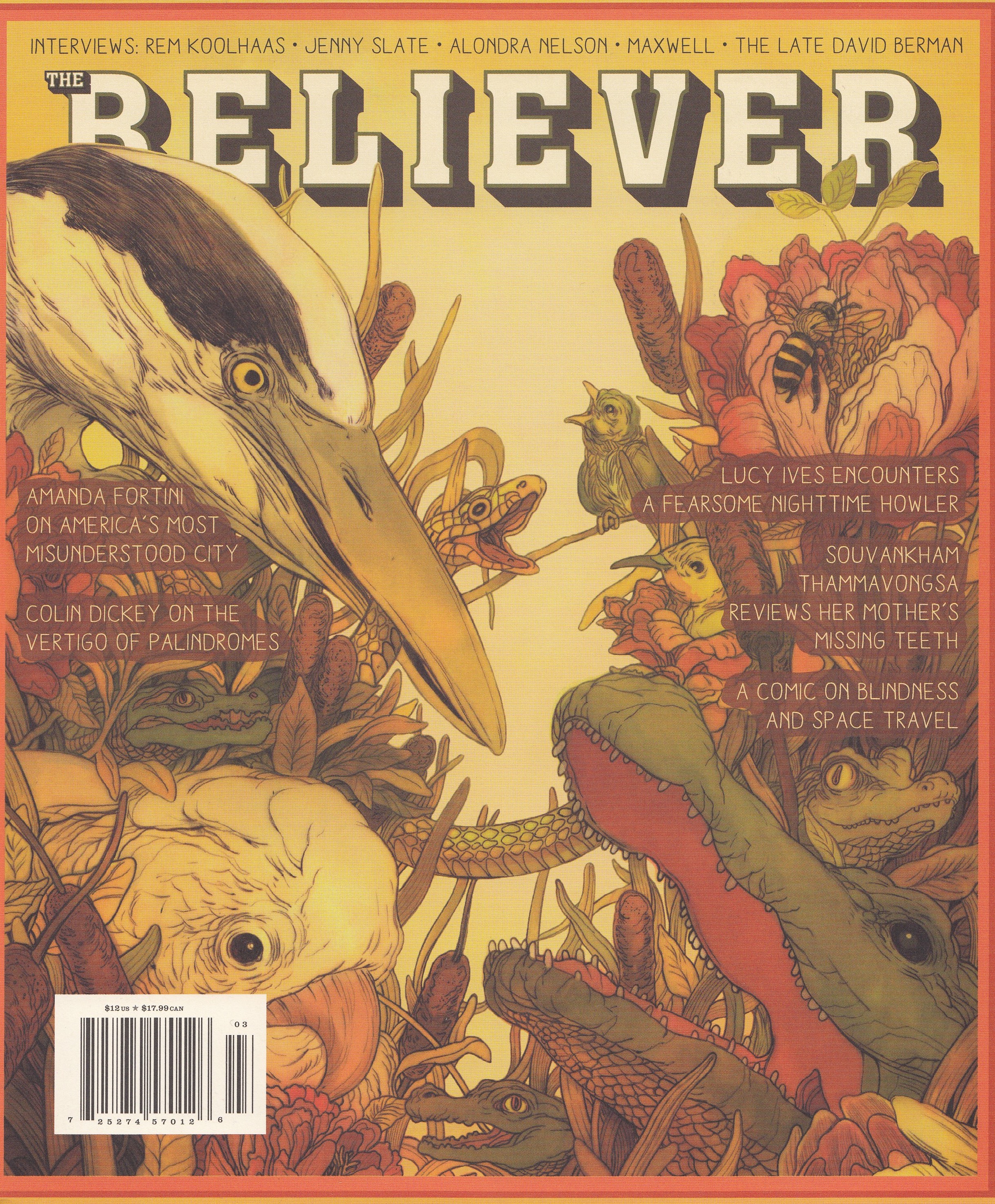

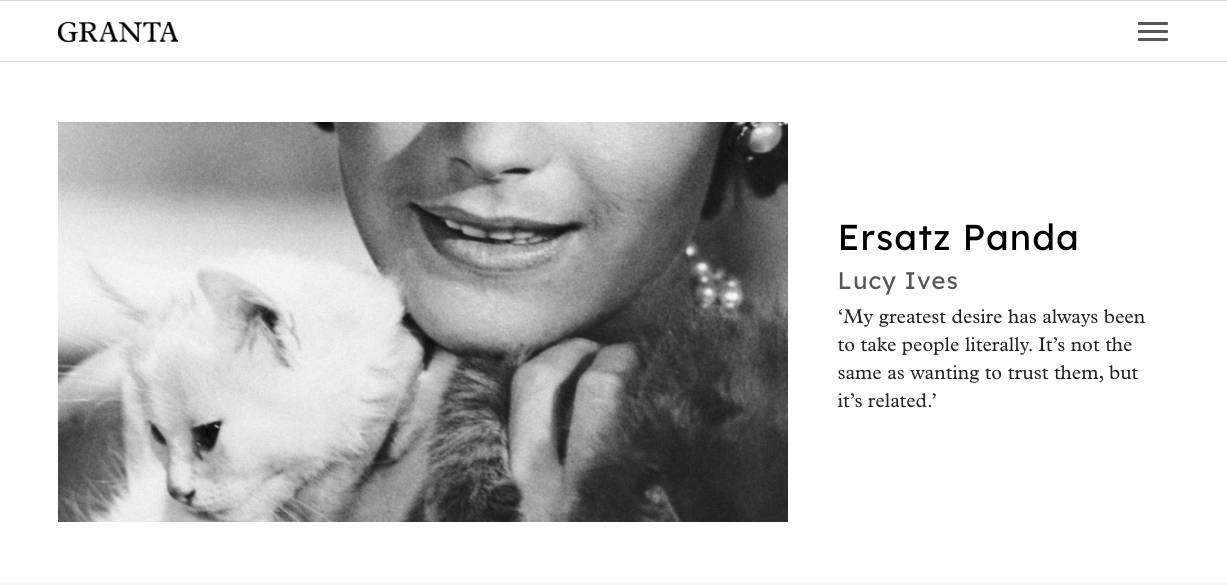

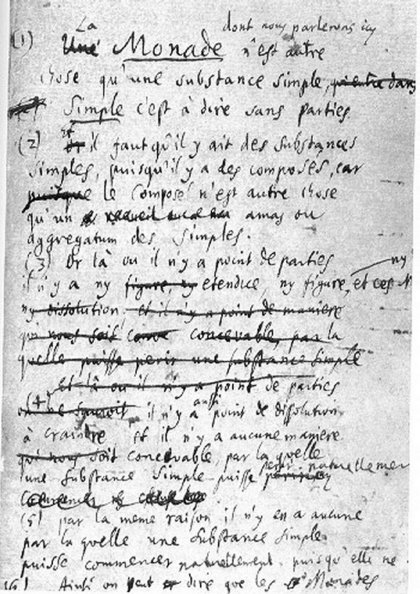

There were two main things I was doing during the time I was not working at the temp agency, or sleeping, or eating, or experiencing married sex, and these were: 1., translating French Symbolist poetry, and, 2., trawling Craigslist for employment. Specifically, I was interested in Mallarmé, whom I considered glamorous as well as difficult. Anyway, it was something I could talk about in mixed company. It was something that got people to leave me alone. “She’s translating Mallarmé,” the man I was married to said. After this, I was left to my own devices and at liberty to navigate over to some listings.

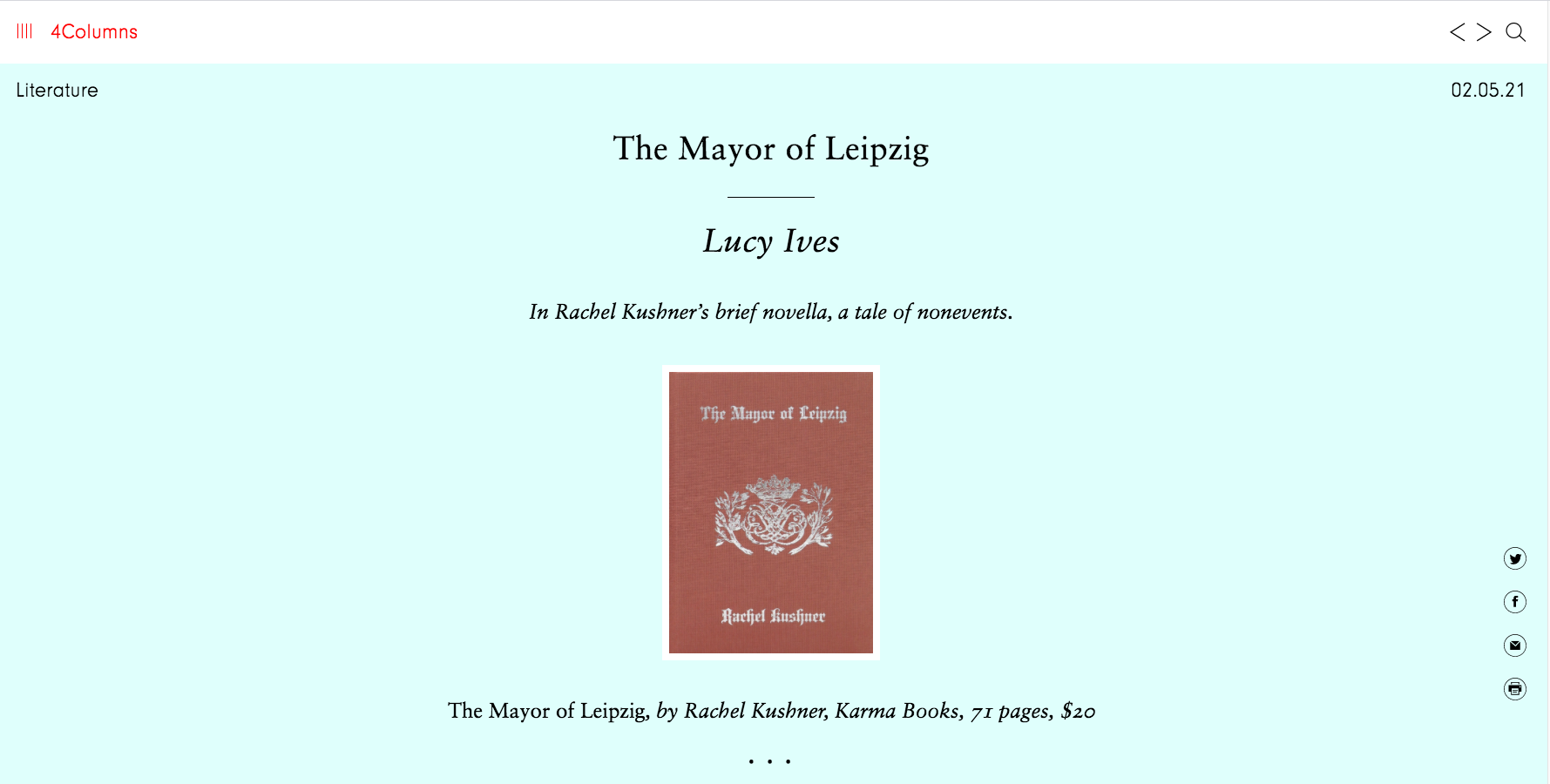

When the American poet Frank O’Hara was pretty young, he made a translation of Mallarmé’s poem, “Un coup de dés.” It was something I liked to look at. I could contemplate the nature of fame. This was, by the way, before Meditations in an Emergency appeared in a scene in Mad Men and became, if briefly, a bestseller. O’Hara was one of the few poets the man I was married to had read, and he seemed to have romantic feelings for him. There was, leaning in an alcove in the entrance to our apartment, a bent postcard featuring a black-and-white photo of O’Hara: one of the only decorative additions to the place not made by me.

The man I was married to returned catatonic from his excursions with the ex-Mormon. He tapped his fingers in his sleep and ground his teeth.

I got out of bed. It was 2:35 am.

Beside my computer sat O’Hara’s Early Writing. I admit there’s a way I look a little like him; we have the same sad eyes. His translation begins, “a throw of the dice Even when thrown in eternal circumstances in the midst of a wreck be It that the abysm whitened displays furious….”

Abysm, I thought.

But I was only pretending to think about literature. I was on Craigslist and responding to an ad.

I wrote:

To Whom It May Concern,

I am a recent graduate of XXXXXXX University (20XX) and the University of XXXX (20XX) who would love to craft some gripping, sentimental, and definitely erotic diary entries for you.

Please find a resume and several recent movie reviews (www.flashfilm.com) attached.

Thanks!

●

The next day I went to work and in the evening there came a reply:

Hello

Thank you for your interest in our little project. We are developing a small artistic website where we shoot some erotic pictures and erotic videos of a few girls. Each girl has 5 or 6 photo shoots with some video and an interview. We need to create a diary for a few of them. This diary would consist of 2 parts:

ONE: Actual blog (e.g. day 1…. Day 2…. Etc…). Some days should have some connection to the photo shoots, but generally it’s a very creative job. The only other condition is that there should be quite a bit of erotic content.

TWO: Also all the photos (and some of them could be repetitive) need some description. However, you can be creative here as well. Your description doesn’t necessarily need to describe the picture… (e.g. if a girl drinks coffee you might right something about her memories of the past, if she kisses you can talk about texture of her lips etc…. etc…).

The total work is about 10 pages (up or down 1 or 2). Total pay for one diary is around $100.

Website is www.fotoconfessions.com

login: confessor

pwd: first

(it’s operating only partially at this point but you’ll get the general concept, take a look at the timeline on top of the page that allows you to go over to different entries. Also it’s better to use explorer than firefox) Most of the girls need a diary. Please write back if you are interested.

Sincerely,

Lev

I held my breath. I had that feeling I had so often in high school, as of a tracking shot.

Dear Lev, I began typing.

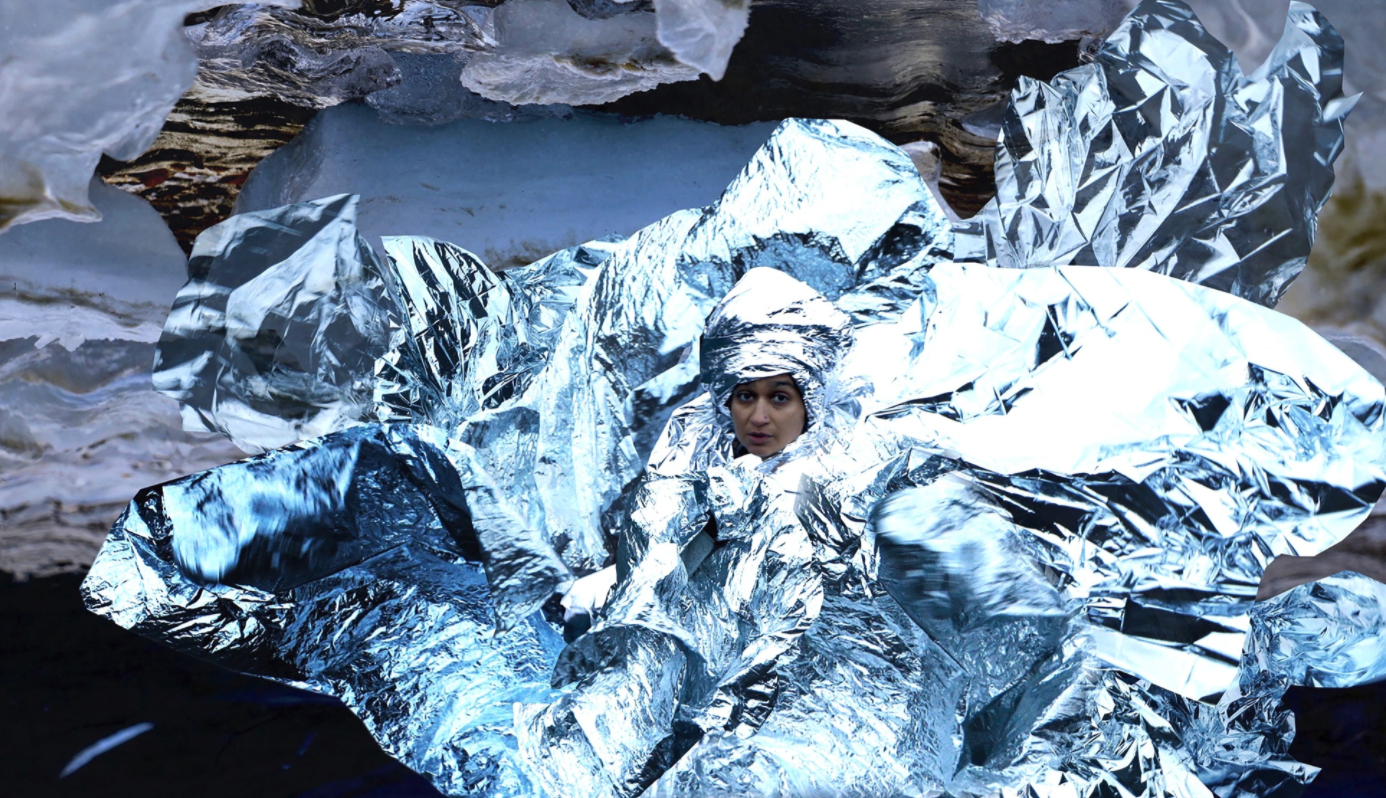

“I want,” I thought that night, “to be free. But freedom is an intellectual demand and, as such, has nothing to do with pleasure.” Far, far below, there was some sort of silvery substance. I could see it glittering there. Truthful, perhaps. Perhaps eternal.

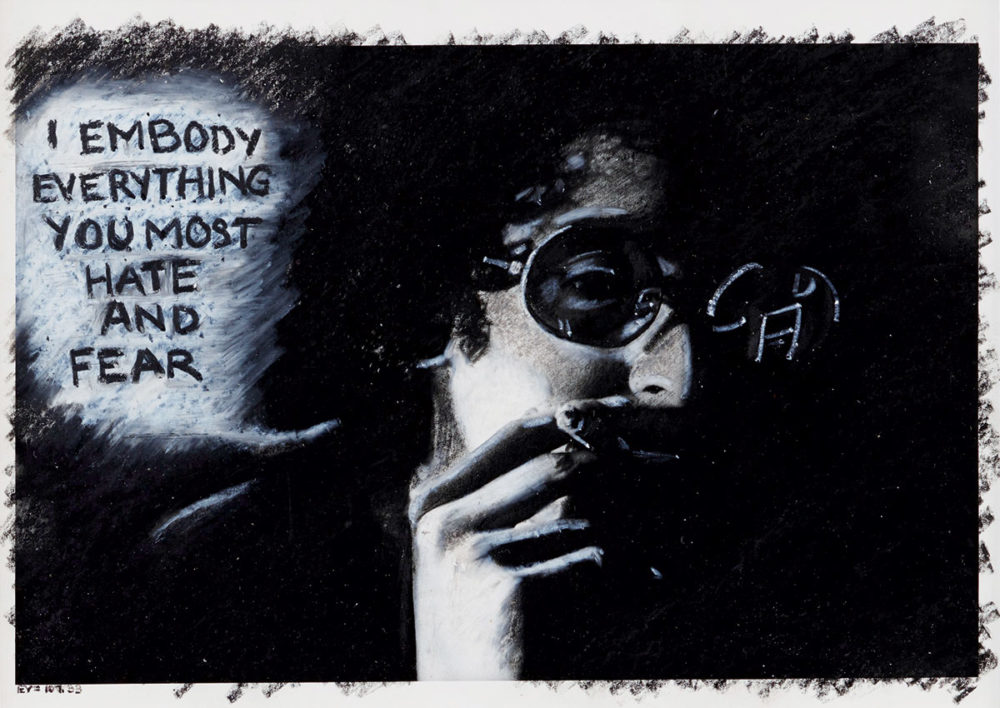

I was not a man.

When I was with the man I was married to, I sometimes wanted him to stop.

“Don’t come,” he would tell me.

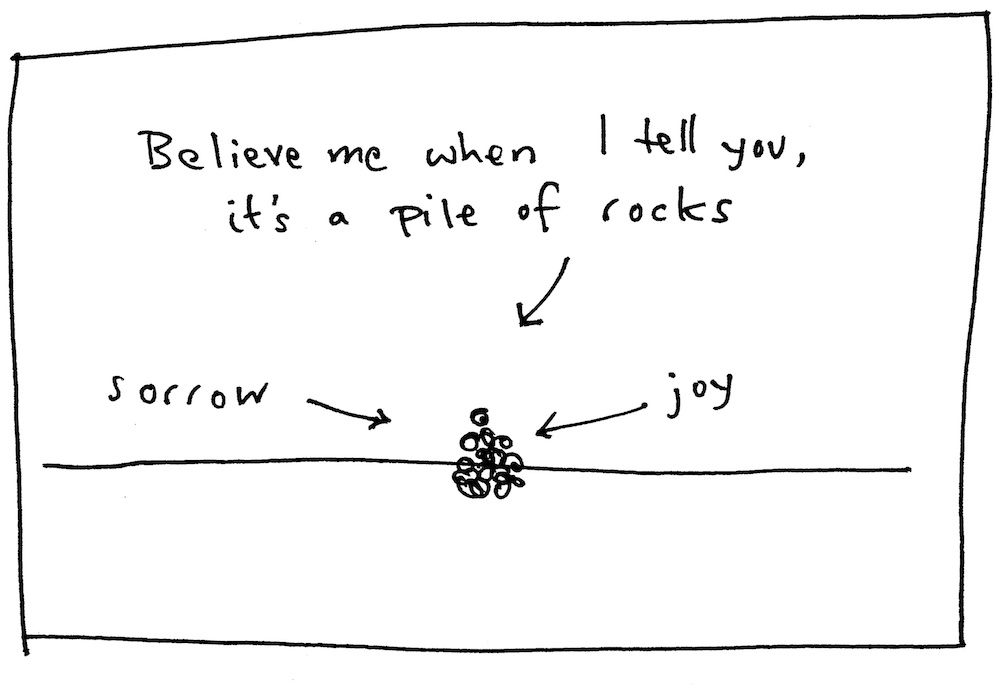

Pleasure was a tiny wall in the void, yet the void inhabited it.

In the midst of an unspeakable orgasm, I felt panic, then what I believed was the nearness of god.

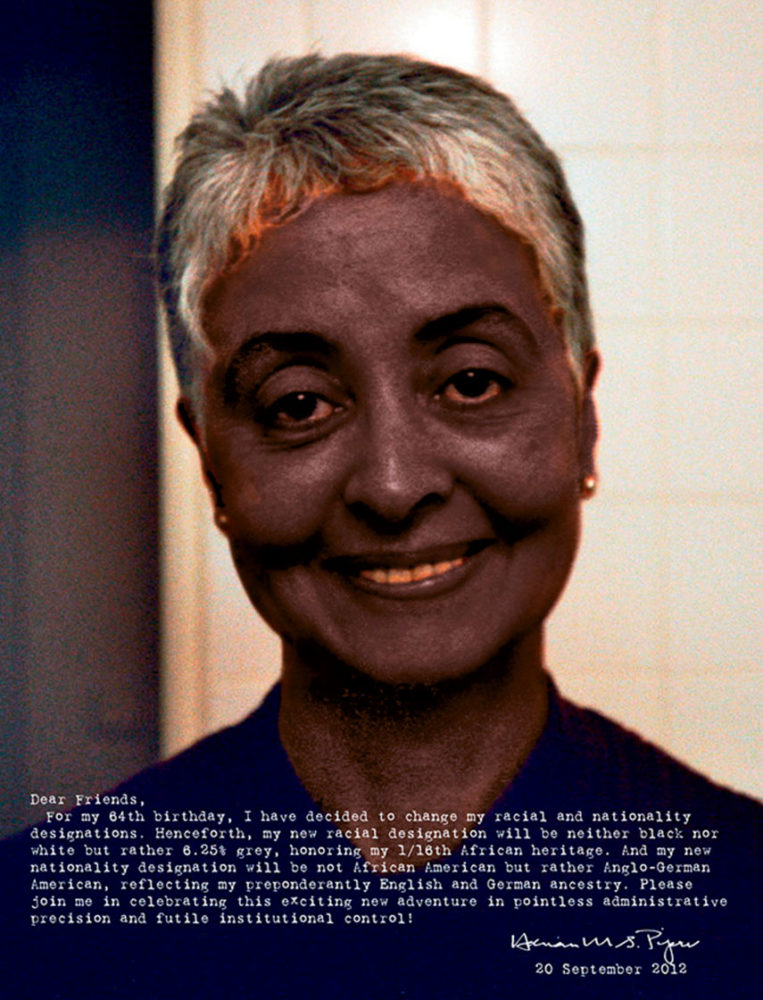

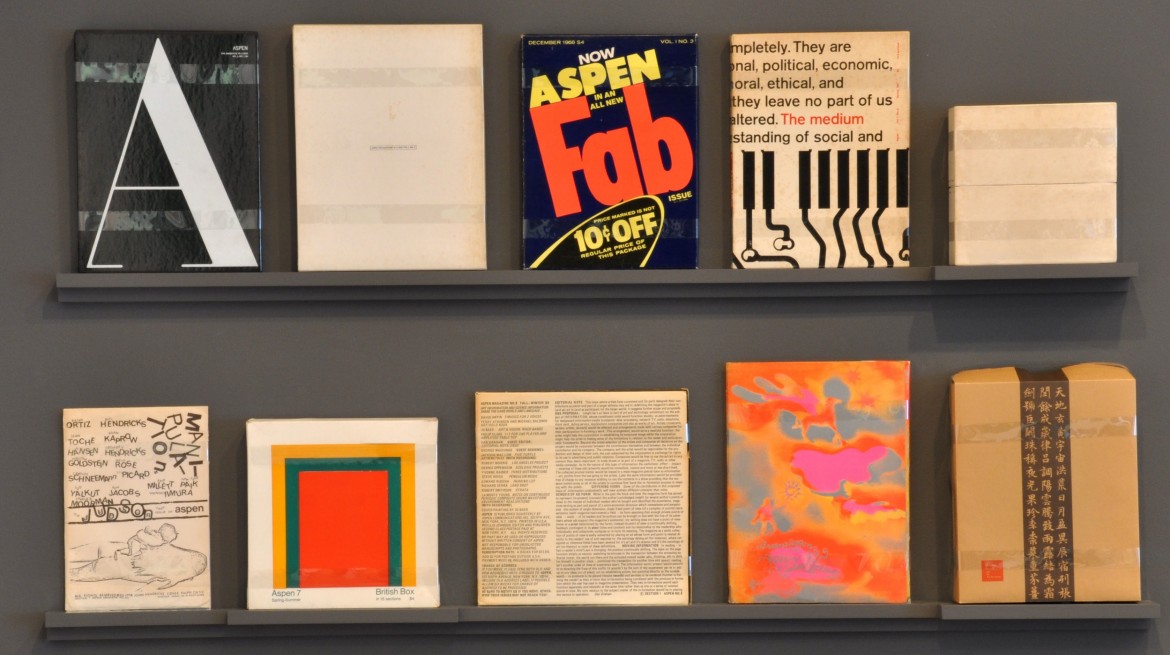

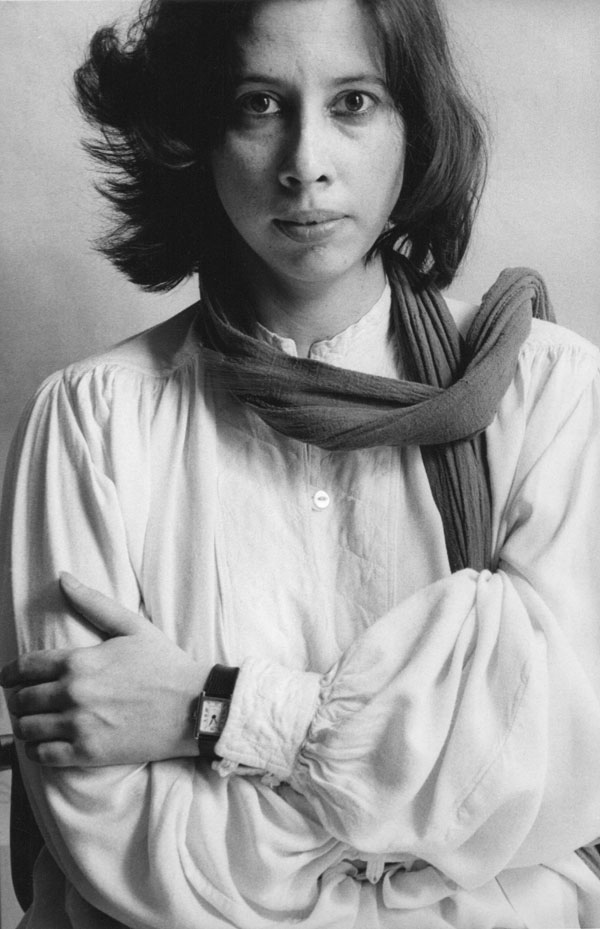

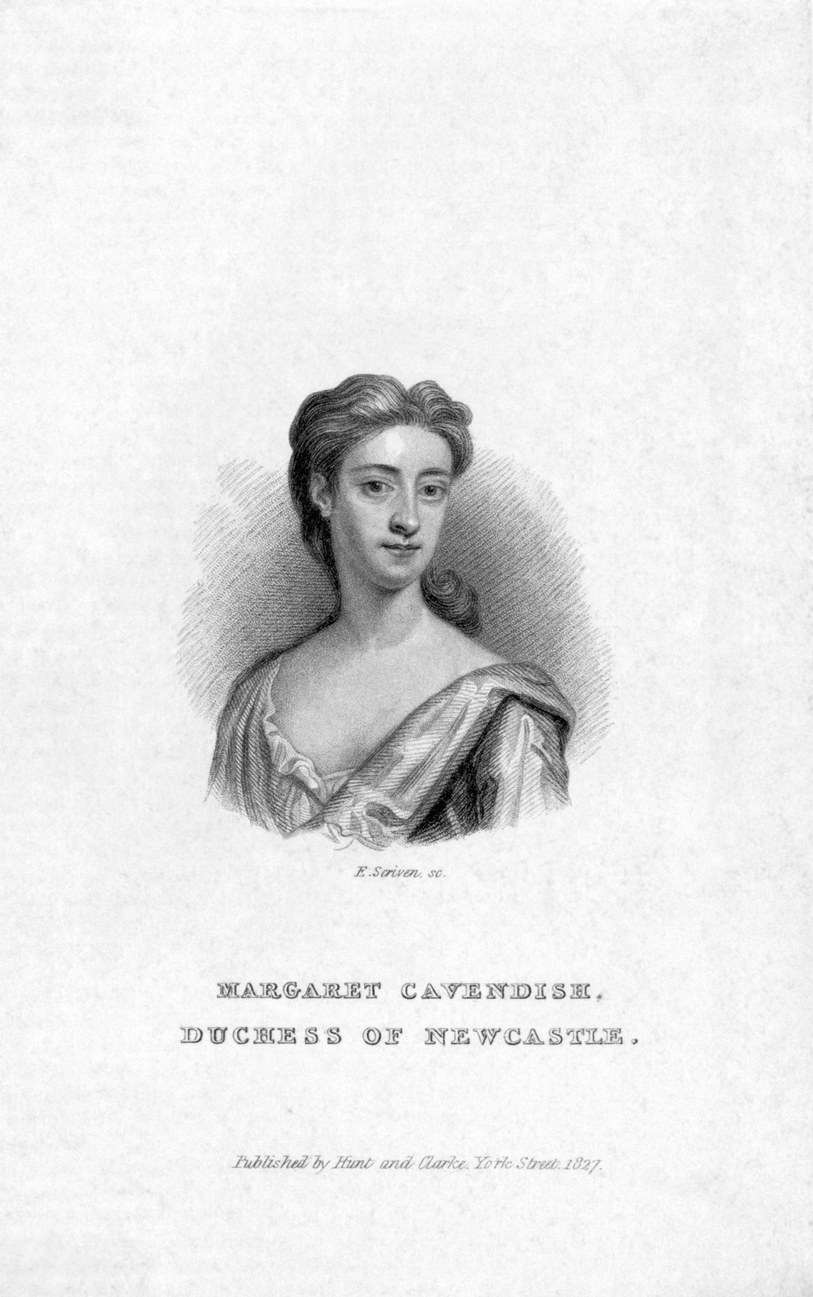

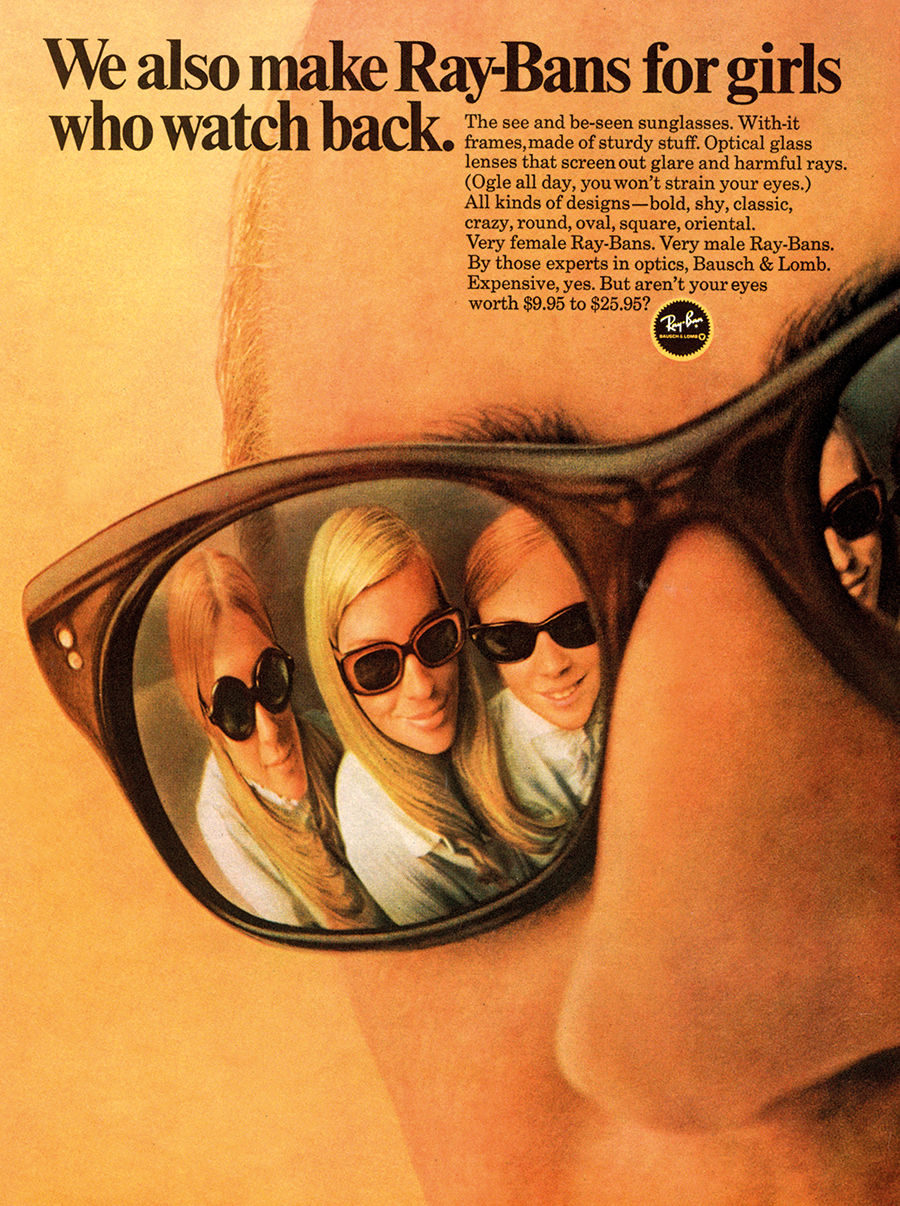

I sometimes wondered what Mallarmé knew about this. In 1874, Mallarmé had pseudonymously written all the articles for eight issues of a women’s fashion magazine called La dernière mode (The Latest Fashion). He became a variety of fictional authors of occasional prose, some male, some not. He was, among others, a Marguerite de Ponty, a Miss Satin, someone named “Ix,” and Le Chef de bouche chez Brébant. These endeavors seemed completely ecstatic.

I was still writing to Lev. It was very late. I could only manage a single sentence: Please let me know how I can get started.

●

The man I was married to was sometimes in a sort of trance, and I did not understand, at the time, that such trances are given to people by their families.

I remember sitting with him in traffic, as a spell of rage overcame me. There was furniture tied to the roof. I was driving and could not speak.

The rage was dense and specific and had a syntax. The rage said, “Your life has no ceiling and no walls and no floor.”

What I interpreted this to mean was that my life might not be my life. I might have wandered into someone else’s story and was now failing to cease residing there. Every day, when I woke up, I failed. It was hard to understand how one could live a life that was not one’s own without having any intention to do so, but here I was, letting such things come to pass.

In traffic, in the car, in one of his trances, furniture tied to the roof, the man I was married to observed my rage. He observed my inability to speak.

“What are you thinking?” he wanted to know.

I could not speak.

“You can’t speak,” he said, smiling. “You can’t even talk right now.”

Traffic loosened and I navigated to a parking spot.

You aren’t supposed to talk about these things, the various ways he impaled me, the stars I saw.

There was a soft part to this, and there was something else.

●

I received a reply from Lev:

Please take a girl named Alyssa and do 1/2 page of a diary and 3-4 captions under the pictures. Send it to me and we’ll get started.

Thank you

I did not talk about this with anyone. I felt a brief joy. In the morning, I went to work.

At work, the Australian was massive and upsettingly well formed. He was a terrible person and seemed to like walking past my desk. It was a common route for just about everyone and he needed no excuse.

“How’s the weather?”

This was funny because I had no access to windows.

Later on, retrieving files from the bottom of some complex cabinet, bent over, I was approached by a more seasoned member of the staff, someone high up in billing. “That’s quite a system you’ve got there,” he told me, a reference, one could suppose, to the administrative code of colors and endless number chains with which the folders that were my domain were labeled.

I could not speak. But then I told him, “Yes. Yes, it is.” And rose to face him.

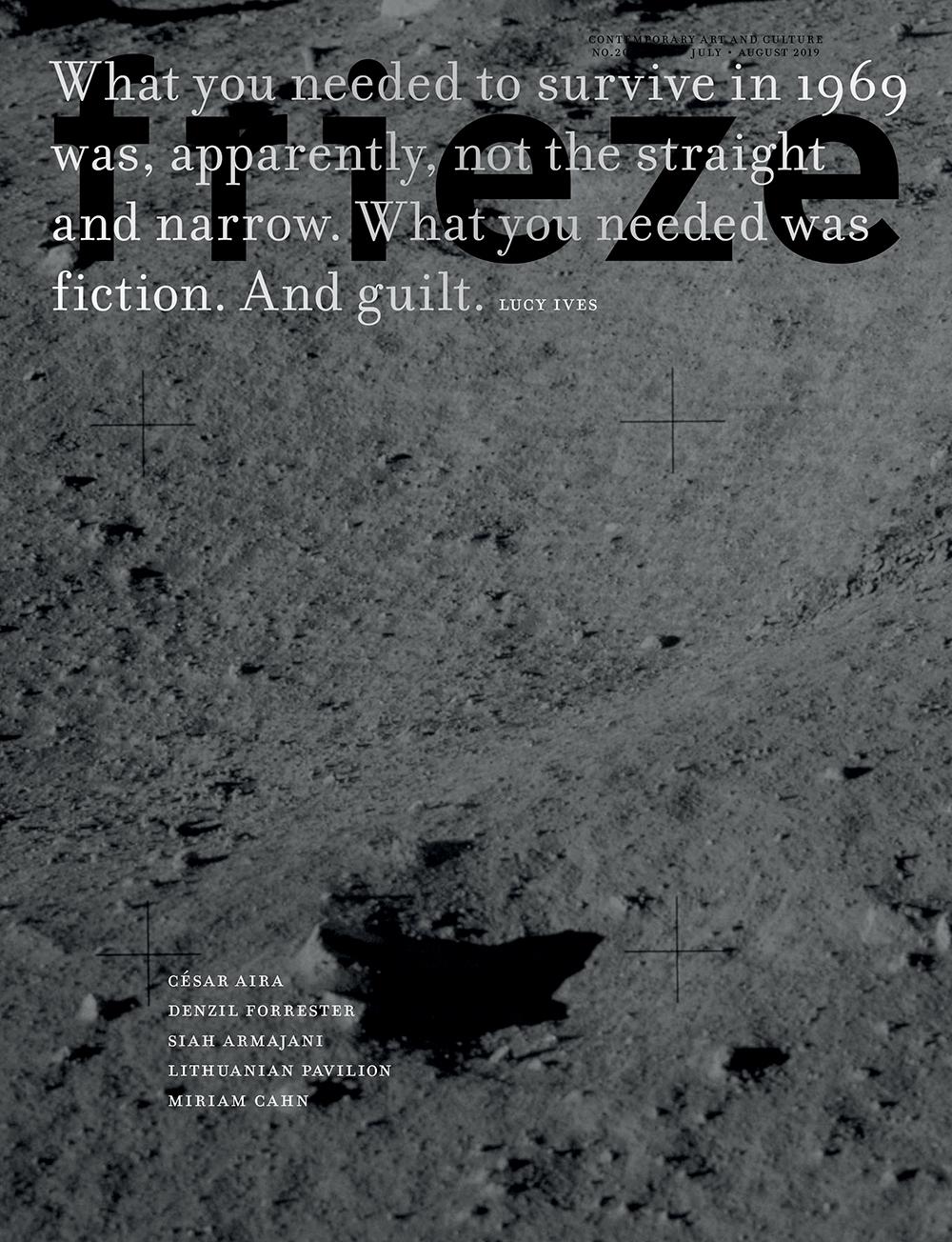

Mallarmé loved foam. He loved something about the sea, the way it hisses in retreat, the way it is a glossy sheet of numbers, constantly multiplying and taking roots and falling into the pit of itself.

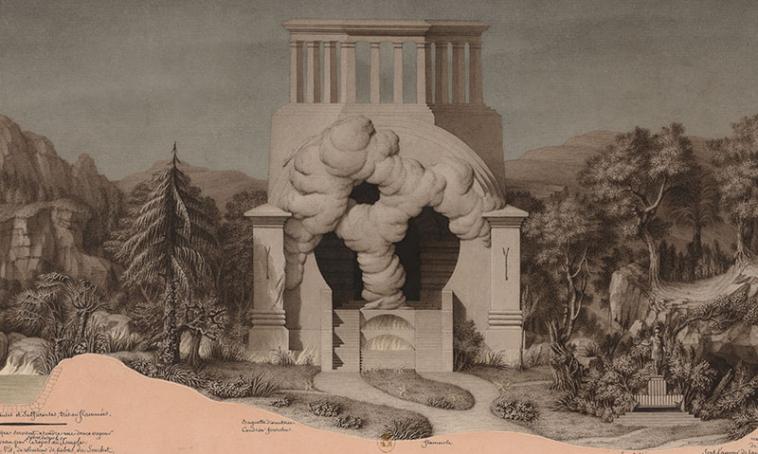

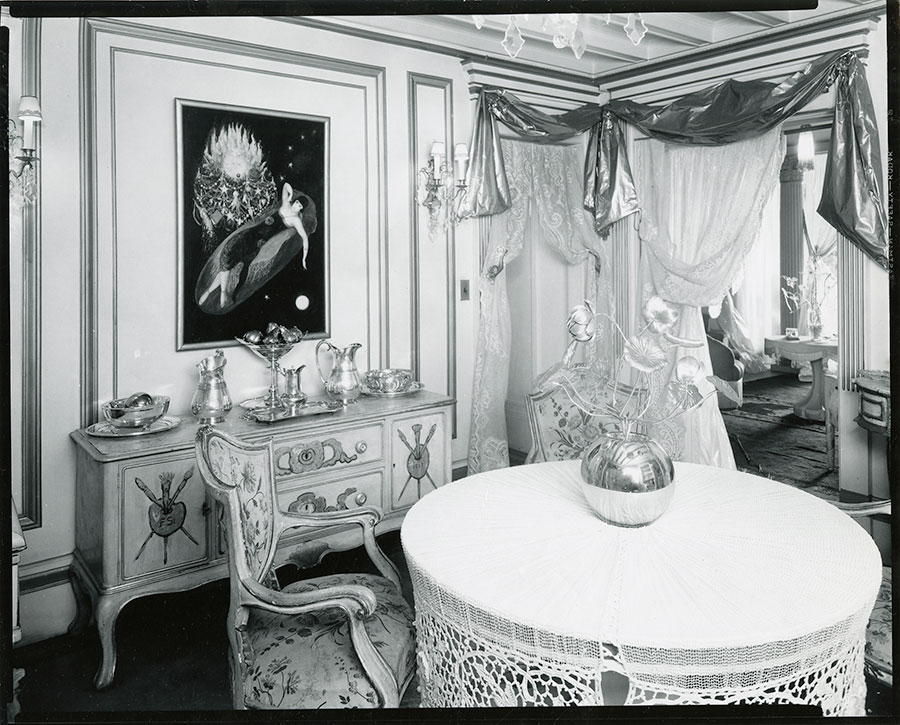

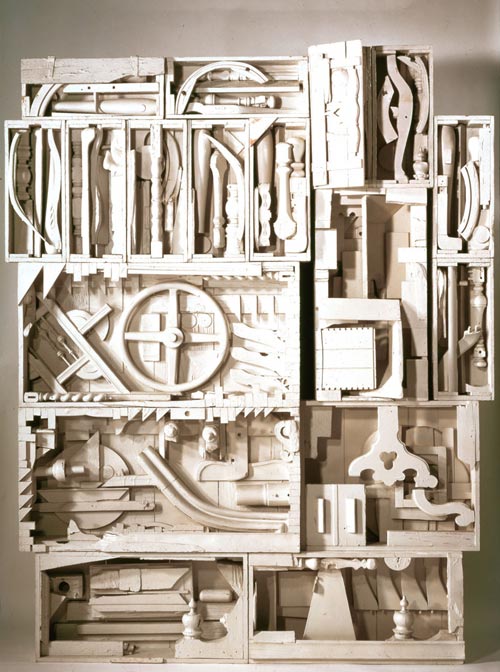

People seem to think that the shipwreck is the thing, but that’s just wishful thinking. The shipwreck is something like a statue; it’s not anything, but it can trick us. If Mallarmé had lived during the golden age of installation art (which, by the way, is ongoing), he might have built some sort of room. The shipwreck is a prop, an echo, a decoration from a long-ago-concluded party. We don’t know it’s not an origin. We don’t know it’s not what happened. We keep it as a sign or proof. We set it as a seal upon our foreheads and go on living.

●

The man I was married to and I went for walks along the Pacific.

No one could say our relationship was devoid of fantasy.

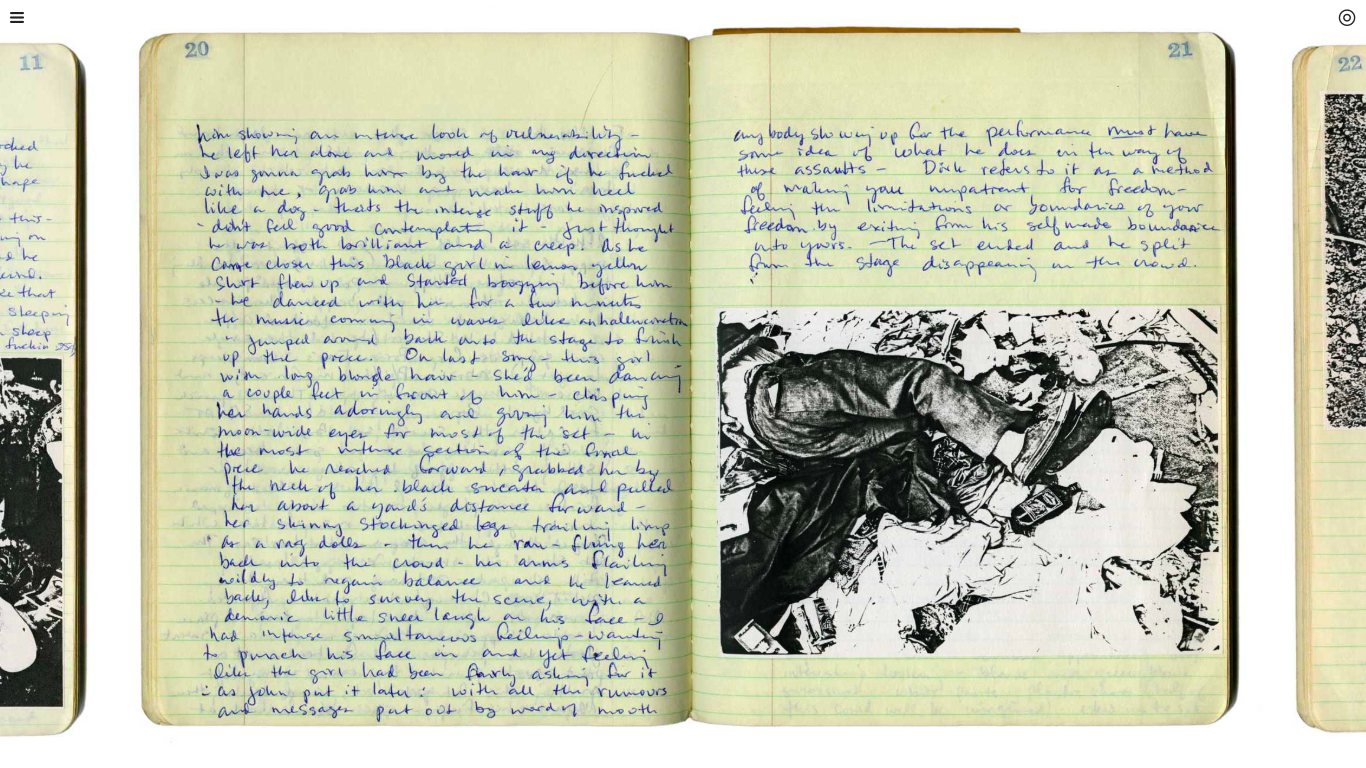

He liked to tell me about the activities of the ex-Mormon. He was learning a lot during their narcotic nights. They’d get as high as humanly possible, then go to a park to break things and talk.

The ex-Mormon was apparently footing the bill. The man I was married to explained that the ex-Mormon was extremely canny. He wasn’t an average person and had long ago figured this out about himself. The ex-Mormon was okay with this. He did not force himself to conform.

The man I was married to examined a pair of flat stones. He made them click and skipped one.

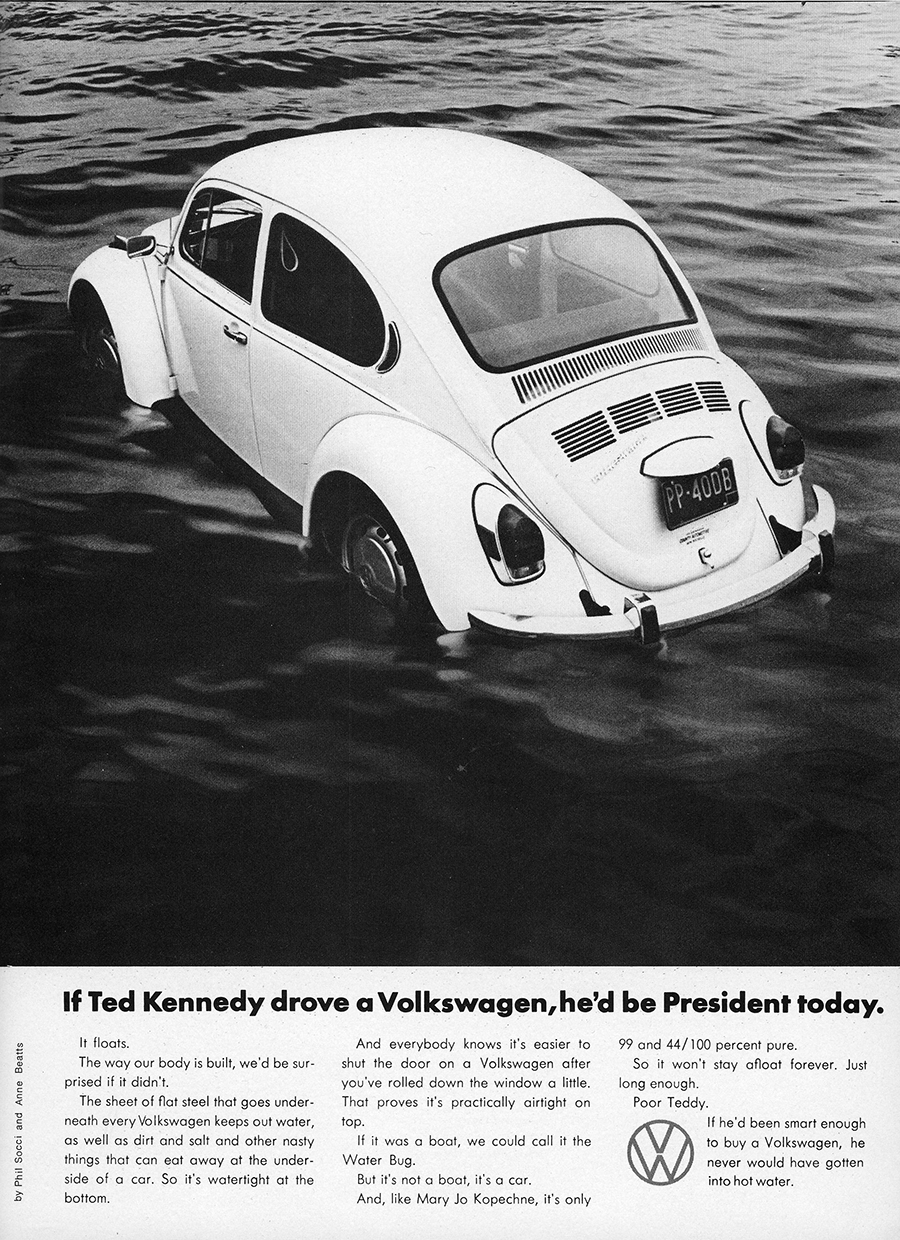

“He’s ‘gay for pay,’” the man I was married to said. He described a scene in a recent pornographic video the ex-Mormon had been featured in, in which the ex-Mormon was slung up in a swing. Everyone was dressed as a clown. The ex-Mormon made $5000.

“The great thing is, you can’t see his face. With the makeup. It’s this crazy niche.”

The man I was married to continued to skip stones. “Maybe you should try it,” he said.

It was the close of a warm day in early October. The sun was doing flattering things to the earth and air.

I was thinking about how there are so many shipwrecks in poetry, and I was also thinking about how Frank O’Hara died on a beach, hit by a dune buggy. It’s a death that seems so wanton, so flimsy, like it has to be a suicide. O’Hara didn’t die right away. He was young, forty. He died later, of injuries.

I realized, suddenly, that the ex-Mormon was a handsome man. He wasn’t a bone-snapping killer like the Australian, but he, too, was attractive.

●

I wrote to Lev:

Hi Lev,

Here are captions for the spread that begins, “I am sleeping”:

Line 1. Mmm. Such a beautiful dream, I’m in a grove of banana trees!

Line 2. Oh well, there’s the alarm! Guess I’m just going to have to find a way to make that dream a reality. Wow, feel a little sore from yesterday. Just thinking of how tight Bobby pulled those straps…

Line 3. Just wish I had someone here. Someone like you. Who knows exactly what I like and how to give it to me.

#

I am not sure what 1/2 page signifies, re: diary, so will give you ~100wrds and hope that’s what you had in mind:

I was trying to get in touch with Bobby all day. I have no idea where he was. It started to get late. I was so lonely that I got dressed up in my silky corset and lace-up boots. But I didn’t want to be blindfolded, and you can guess why: I went into the bathroom and put one foot up on the edge of the sink, imagining Bobby was there watching me. I got so hot that I went over to the bed to finish myself off. That’s when the doorbell rang. You can guess who it was. I was so happy!

Best,

●

Soon my parents came to visit. Their take on my life with the man I was married to seemed to boil down to a single question, “Why are you poor?”

They took us out to lunch at the most expensive restaurant they could find, where my father insulted the waiter. The napkins had a very high thread count. I kneaded mine below the table. With my right hand I stirred some bisque.

The man I was married to chuckled politely.

My father glanced at a woman passing through another room. “Is that dress rubber?” he wondered, in slow and casual tones.

The man I was married to dutifully transferred his eyes to the mark.

I could not speak.

The woman was wearing a cotton shift.

A pit had opened. Everywhere was iridescent. The pit continued to sink, mechanized and sure.

“What’s wrong?” asked my mother, somewhere.

It was magic.

The pit trembled. I could hear but could not move.

My mother brought the point of her napkin to her lips.

“How could he say that?” I managed, on a breath.

“What did I say?” my father bellowed. He was addressing my mother, who was patting him. “I asked a question about a dress!”

“Relax,” stage-whispered the man I was married to. He put my spoon back into my hand.

●

I would go sometimes to the twenty-four-hour donut shop on the hill above our apartment. It wasn’t a fancy place, but the Boston Creams were good and it had seating. It was owned by a family who didn’t seem optimistic about the state of the world, but they knew a lot of the people who came in and maintained a supportive tone. It was a place where I could go to mourn.

I sat along one of the windows, at a narrow counter. I always had black tea with milk along with my Boston Cream, which I cut into small pieces with a plastic knife in a futile attempt to make it less caloric.

It was usually the same man or his precocious daughter who helped me. They didn’t comment on my repeat visits.

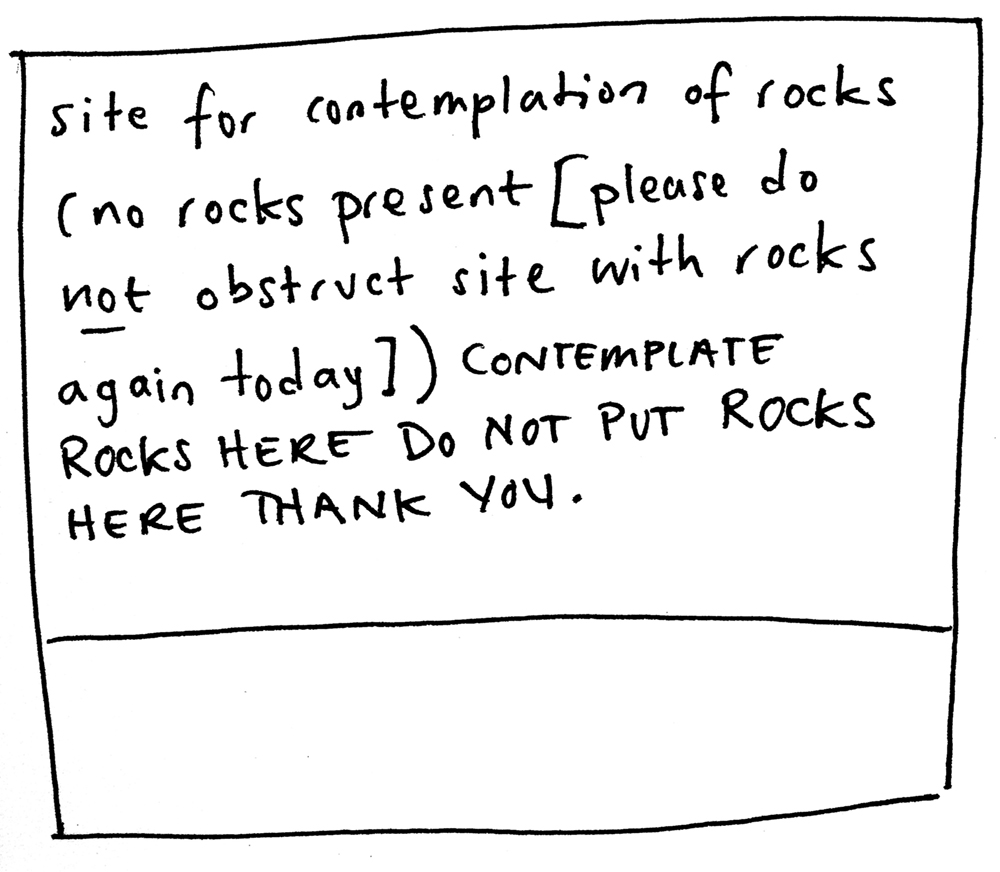

I’d sit along the window and stare at words arranged by Mallarmé. I wrote: Like listening to Genesis read in reverse. Always this sense, Mallarmé’s sentences are occurring in reverse. I kept looking at a certain set of lines: “naufrage cela / direct de l’homme / sans nef.” I wrote: That shipwreck of the man directly without a ship. I put a pair of parentheses around “directly.” I erased the parentheses.

Outside, a tram rumbled by, taking people somewhere with mystifying inefficiency.

One evening the man at the donut shop asked, “How old are you?”

I said, because I really wanted to know, “How old do you think I am?”

“You’re 25,” said the man.

“You’re right,” said I.

“Well, have a good night,” he told me.

I walked back down the hill, revising my mental list of shipwrecks in poetry.

●

Lev said:

I like what you wrote. So, let’s start with Alyssa.

To recap: About 7 pages of diary (up or down a bit is ok.) We measure page in a standard way. Then captions.

Please write 3-4 lines per row of photos. e.g. [1 row: It was so nice to see Bobby….] Then second row etc…

We’ll end up with plus or minus three pages.

Consider yourself hired for Alyssa’s diary. If all is well, we’ll hire you for the next one.

If you have questions you can reach me by 415.XXX.XXXX

●

Here are the shipwrecks I know of in poetry:

Odysseus of course had difficulties sailing, as did the apostle Paul, who was shipwrecked four times. John Milton had a good friend named Edward King who died in waters near Wales in the first half of the seventeenth century, and this event inspired “Lycidas,” a poem with the strange formulation, “wat’ry floor.” The poet John Keats died in a sailing mishap and his friend Shelley memorialized him in “Adonais.” Emily Dickinson had a floor, too: “If my Bark sink / ’Tis to another sea — / Mortality’s Ground Floor / Is Immortality.” Gerard Manley Hopkins wrote “The Wreck of the Deutschland,” a poem about the unthinkable and how it is somehow sanctioned by god. And I am leaving out The Tempest by Shakespeare, although I am thinking, too, of Aimé Césaire’s Une Tempête, in which Prospero is at pains to explain to Miranda that the storm and wreck they are observing is no more than a play. The American poet and labor organizer George Oppen wrote of “The unearthly bonds / Of the singular / Which is the bright light of shipwreck,” and another American, Hannah Weiner, said, “I am a complete wreck.”

And there is Mallarmé.

●

At the temp agency there was a woman in her early thirties. She ironed her hair and wore a pantsuit with a seventies attitude though the pantsuit came from Ann Taylor. She was undeniably chic and had a good position and was married to someone very rich. She was interested that I, too, was married.

“Are you planning to have children?”

I said something about how I wasn’t sure of anything yet, which she took to be an expression of appreciation for the corporate ladder. She began to reel off names of persons I would need to meet.

I waited for an opening. “Are you planning to have children?”

“Oh yes,” she said. “We start this summer.”

“How wonderful,” I told her, feeling adult.

“Look at my ring,” she offered, suddenly trusting me. “Isn’t it amazing? It’s Cartier. They only made like ten of them. It’s brushed titanium with platinum and sapphire and black opal. I like it so much more than a single setting, and it’s so unique. I was so, so touched when my husband suggested it.”

“Wow,” I said.

“Can I see yours?”

“It’s just plain gold.”

“Wow,” she told me.

“I picked it out.”

“Well,” she said, handing it back, “I’m sure your husband loves you more than that.”

●

I wrote to Lev:

sorry this has taken me so long, it will usually only take me 24hrs to turn over an assignment of this length. please let me know about payment and if you have more diaries you need written.

thanks!

#

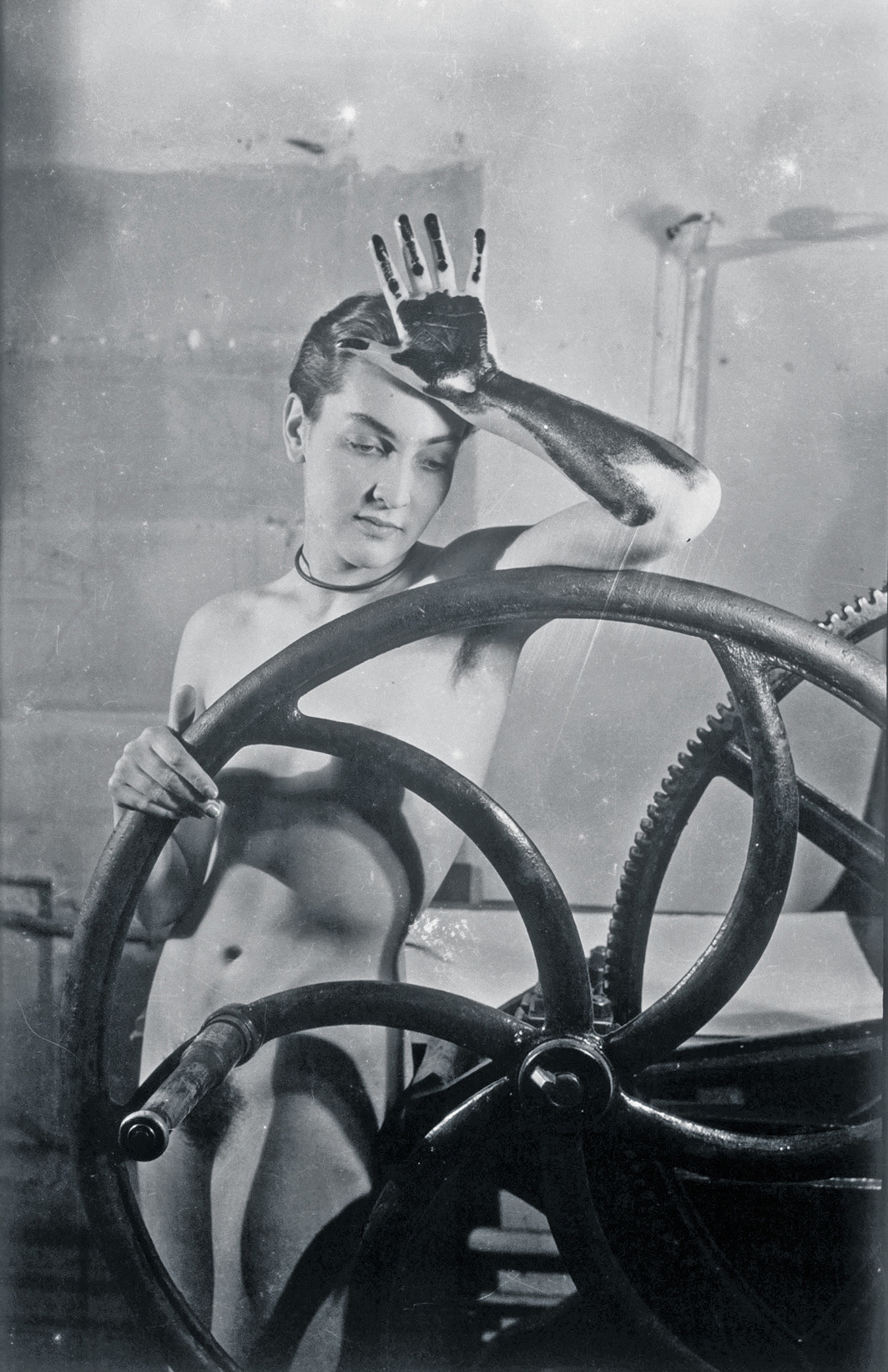

One. Dear Diary, I woke up this morning and didn’t know where I was. The first thing I noticed, though, was that I couldn’t open my eyes. There was something heavy and kind of cool covering them. Probably a leather blindfold. Maybe it was weighted somehow, like there was metal inside it. I noticed also that my wrists were a little tender (not to mention certain other parts, which I won’t mention, because I’m sure you’re thinking about them already). I moved my arms around experimentally. They were stretched away from my body, securely fastened by some type of leather cuff or straps to the posts of my bed. I wiggled. I could feel now that my legs were also restrained, in a predictable position, and that I was wearing a leather harness that cut into the skin at my hips, but not in a totally unpleasant way.

It was kind of hard to breathe. I lay there, pulling in short sips of air. I thought, and I don’t quite know how to tell you this, that I could feel drops of water on my face and maybe on my chest and stomach. Then the water began to really fall. I don’t know where it came from. It was warm and I felt myself being bathed but I had to struggle to get air. The water was everywhere, running over me, and then it stopped.

“Bobby?” I whispered.

“No,” said a female voice. “This isn’t Bobby.”

Two. I think I was hallucinating yesterday. Maybe dreaming. I don’t know what it was. I woke up again, late, and there was nothing unusual going on. The only thing was, my hair was damp. I guess it could have been sweat.

I got up, feeling angry at Bobby. I wrote him an email telling him things were getting out of hand and I refused to see him that day or ever again. I know that sounds a little unfair—but I want Bobby to know, just in case he doesn’t understand, that he can’t just sneak up on me, psychologically speaking, without there being repercussions. I mean, my mind is my temple, and my experience with men has taught me that you have to make it a little hard for them! And in Bobby’s case, well, you can guess…how I feel…. The problem is, I might be an addict. But never mind all that, because I had an amazing adventure today.

I decided to treat myself to a movie in the afternoon. I worked out all morning and took a long hot shower. Then I put on moisturizer (almond butter, it’s the only kind I’ll use), slipped on one of my favorite panties (nothin’ but string, baby!), and got into one of my velour lounge-suits. I didn’t wear a bra because, well, it was just one of those days—and I like the feeling of the material. Oh, and I wore lots of lipgloss.

The movie was this cheesy spy-thriller I’ve been wanting to see for a while; I guess I kind of have a thing for the lead actor (it’s the way he’s so good with his hands!). I was just starting to get bored when I noticed this cute boy sit down in my aisle two seats away from me. The theater was very dark, and there weren’t too many other people there. I waited to see if he’d notice me, and when he did, I very slowly started sliding down the zipper on my top until it was down below my bellybutton. Then I slipped one hand in. Now I could tell I had his attention, so I put my hand in my pants. I was imagining what he would think about my underwear. I wished we were somewhere else. But I thought I’d settle for the here and now. I think he knew what I had in mind, because he got up and came over and sat next to me to help out.

Three. I have basically forgiven Bobby. Tonight I let him take me out to dinner. It was a simple affair. I wore a new pantsuit with a corset-top that felt wonderfully tight. We ate at a small French restaurant, it had maybe 10 tables. I ordered oysters and roast chicken and then salad. Bobby just sat there watching me eat. He didn’t even touch his wine. The whole time I felt he was looking at me in a new way, as if he had discovered he desired me differently since I’d told him about what I’d dreamed the other morning and how it had upset me so much I might never want to see him again. I was almost afraid of him. It was like he knew something about me that he’d never known before, and maybe it was something no one else had ever been able to discover. What could it be? I did not invite Bobby home with me. I am waiting until tomorrow to decide what to do.

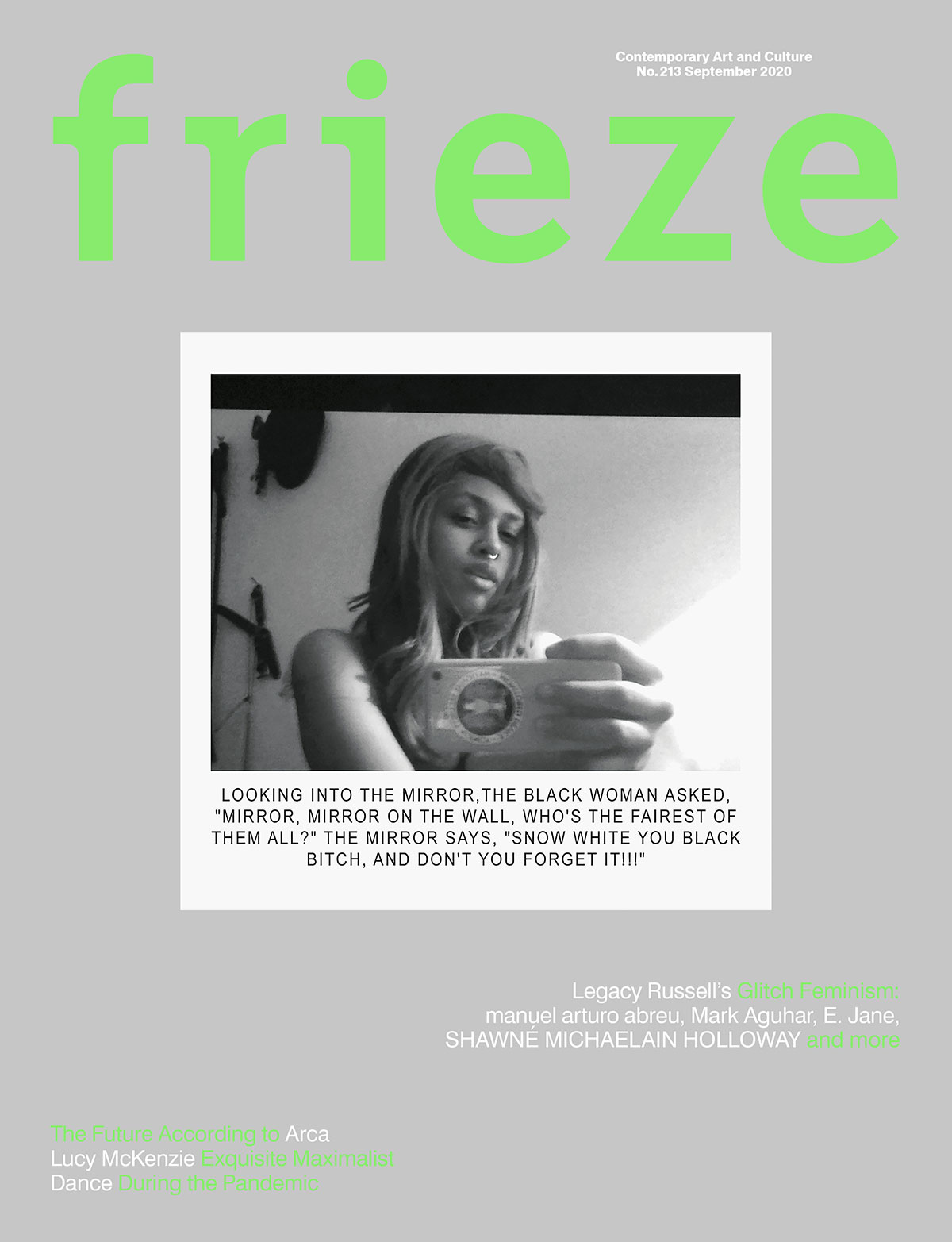

Four. Late last night I started missing Bobby, and I decided to make a little movie for him. I got the big mirror off of the wall in my bedroom and set it up on the floor with the camera resting on top. I decided this was going to be a movie all about my fears. I sat down on the carpet in my underwear, with a box of matches. I turned on the camera and started taking off my bra and panties very slowly. Once I was naked, I lit a match. I just sat there, watching it burn down to my fingertips in the mirror. When it started to burn me, I looked at the image of myself. I watched myself wince and flinch. I made myself keep looking even though it hurt. There started to be this other part of me there, then, just as I knew there would. I could already feel myself starting to lose control. My hands were shaking, but I lit another match and held it. I was watching myself do this. I brought it down to my knee. But then I jumped up and shut the camera off and went and dropped the matches in the sink and turned the faucet on full blast.

Five. I emailed the movie to Bobby. I think he liked it. He told me it was “deep.” He’s asked me if I will make another one for him or tell him more about my fantasies. I suddenly feel shy again, as if maybe I’m revealing too much about myself. I do have another fantasy to share with Bobby, but I’m not sure if I should. Here it is, Dear Diary. Maybe you can help me decide what I should do. I want to be taking a shower, when Bobby suddenly enters my apartment and then the bathroom. He picks me up and carries me to my bed, where he blindfolds me, ties my hands, ties my ankles. And then he leaves. He just leaves me there. And I can’t move. And when he leaves he locks the door. And then he goes and gets boards and nails them over the door. And then he goes and gets bricks and mortar and bricks over the wood. And then he goes and gets stucco and paint and makes a perfect wall. I can hear him working. And then there is silence and I cannot move and I feel the weight of the bricks on my face even though they’re nowhere near me. They’re so heavy and so cool weighing me down. And it hurts so much and is so peaceful, and during the hundreds of years that pass even Bobby dies and I am completely unknown…

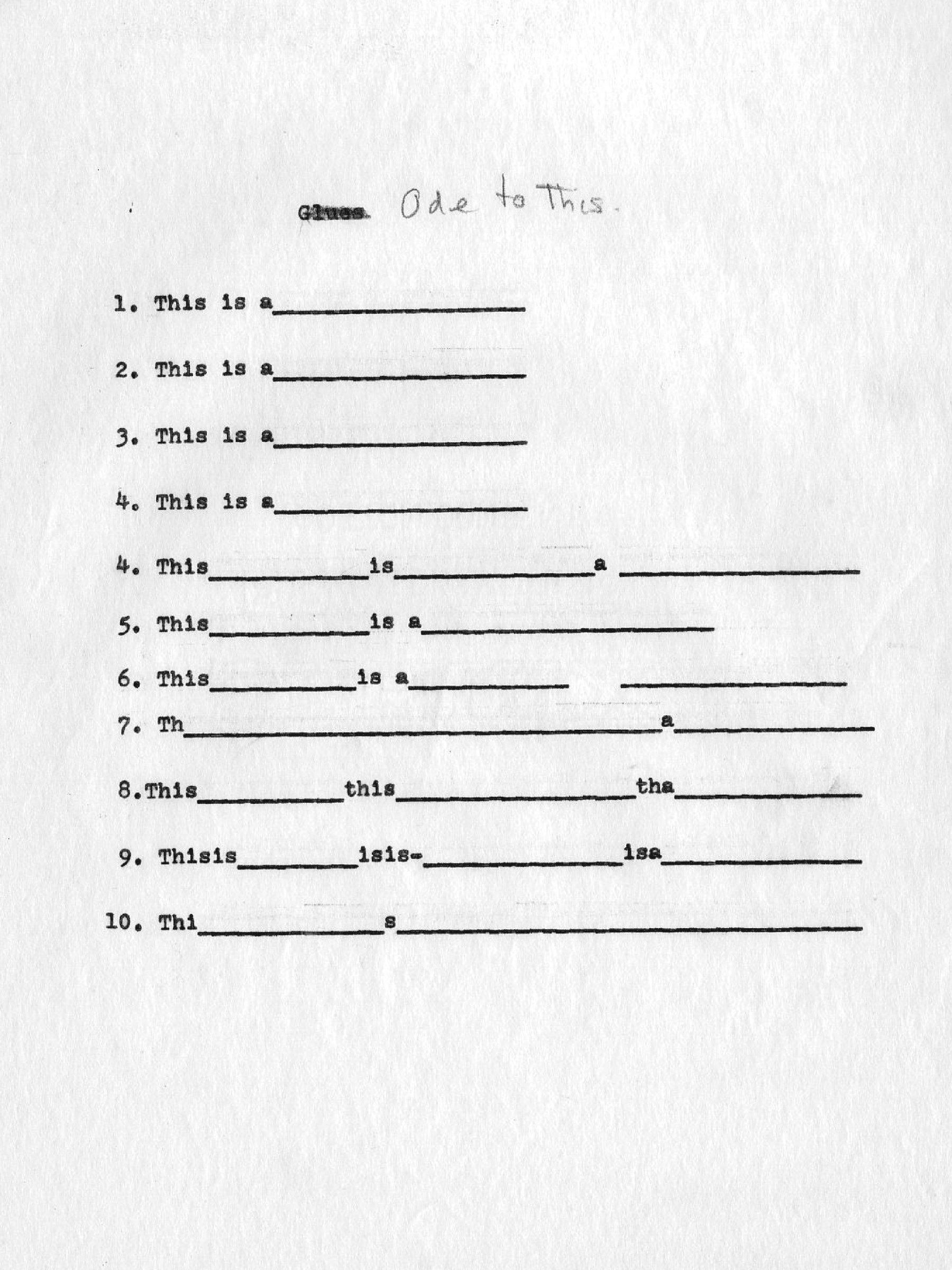

Six. I told Bobby about my new fantasy. I think it definitely excited him. He told me he would come over soon, so I’m just getting ready to see him. I put fresh sheets on the bed, and I’ve been ----------------. I am so excited, I’m almost -------------------. It’s all I can do not to --------------------, but I want to wait for him to --------------------. I think I am going to wear a white dress in the shower so Bobby can tug on it and maybe it will be see-through and --------------------. Or maybe I’ll wear this white -------------------- that doesn’t have -------------------- where -------------------- should be. I should -------------------- my --------------------. I’d like that. Well, I better get the water hot, I think Bobby will be here soon.

●

Lev replied, instantly:

I don’t think you mean “almond butter”

Second, I don’t know what half this is, including the mad lib (?)

Give me a call please

●

I took off early on a Friday, the next day, so I could speak with Lev. I was mortified, but I did not know what else to do.

“Hi, may I please speak to Lev?”

“Yeah, here.”

“Hi.”

“Who’s this?”

“It’s, uh,” I started to say.

“Oh,” he said, “it’s you. Writer girl.”

I made a noise.

“Yeah, one second.” Lev seemed to walk into another room. “Sorry, I’m in the studio. You should come down sometime.”

I didn’t say anything. I wasn’t sure what a pornographer was supposed to sound like. Lev sounded brisk, lucid.

“Okay,” he announced, “I have officially entered the green room. Let me call this thing up.” Time passed. “Okay, looking at it. You have too much investment. That’s what I think.”

“Sure,” I said.

“I like it in some ways. I won’t lie.”

I didn’t say anything. I could tell that Lev was lean. He was not exactly short, but he wasn’t tall, either. He was lean and had a simple countenance.

“Care less and be brutal. How does that sound?”

I didn’t know what to say. “Yes,” I said.

“Yes? Yes is not an answer to my question.” Lev was typing something. “Sorry, one second.”

I waited.

“Okay. I’m back. You understand what this is for? I’m not trying to be a fascist.”

I didn’t say anything.

“I would like it if this works. I would like it if it would work.”

“I get it,” I said.

“You were showing a lot of potential there. You have a nice light touch. But brutal, okay?”

“I want to try again.”

Lev said, “There’s a part of it you understand, right, where it’s a game and it’s something you can look at, but there’s another part, too, where it’s only happening. Do you understand?”

“Yes,” I said.

“The important thing is not to be living in the past.”

“Yes,” I repeated, uncomprehending.

“I was hoping we could work together,” Lev said.

Yes, I was thinking, no.

My face starting shaking and I accidentally hung up.

●

The man I was married to got into an accident on his bicycle. He was coming to an intersection at the bottom of a hill. He went over his handlebars and flew onto the hood of someone’s car. The driver gave him $700 to walk away. He came home to lie in bed with a fuchsia bruise hooked from his left nipple to the center of his back.

The bruise looked like a sickle or thin moon.

“Good job walking away,” I said.

The man I was married to was munching some Bayer, flipping through a tabloid.

“Aaron is leaving,” he said.

This was the ex-Mormon.

“He got a job and needs to relocate. He wants to try it for a year.”

“Is this more acting?”

“No. It’s more textbooks.”

“Weird,” I said.

“Not really. Some uncle set it up. I guess he’s going back in the fold.”

“Maybe they’re running out of men.”

“Maybe,” said the man I was married to. I could tell his injury was bothering him. I sat on the edge of the bed, feeling some of his pain. If I shifted, it would hurt him, I could tell.

I shifted.

The man I was married to did not react.

The tabloid was between us, and the man I was married to turned a page.

BIG CUTS FOR WEALTHY, the tabloid said.

I shifted again.

●

That night we went out with the ex-Mormon to celebrate his new future. The ex-Mormon’s hair was so light it was white in the bar. He was a large, freckled cat. His eyes were pale green, nearly yellow. He was the product of inbreeding, heavy and thin at once, pale and dark, canny and naive. I could tell there was something about humanity that he had come to understand and perhaps accept, that I never would, and I think this made me angrier.

I observed the ex-Mormon, wrapped in his superior narrative, undeniable in spite of his ex-ness. Maybe even the apostates got to go to a private planet with a low-melanin female janitorial staff, after death.

The man I was married to was taking an extra long time in the bathroom, probably because of the injury, but who could say for sure.

I entered into a fresh Maker’s Mark, noting that my tab now constituted a full 90 minutes of my employed labor.

“It’s a job,” the ex-Mormon said, “but I’m planning to like it.”

I realized that he had been talking to me for a little while now about his forthcoming rebirth into the middle class. I hadn’t been listening to him because there was something pounding in my ears. It was the voice I could always hear, once I got wasted.

The Mormon would marry someday and have children, and he knew it. The man I was married to would marry again someday and have children, and he knew it, too. But what was I going to do?

It seemed not to be enough for me, I realized, that possibly I was free, forgetting for a moment about the machinations of capital. I was free and could act, and from my actions would be composed an event. And out of a single event and another event, would be composed yet another event, which was a story.

But beneath these facts, which I could say to myself and hear myself say, and even understand as a style of logic, there was something else.

If I could drink another drink, maybe I could listen to this thing. This was the thing where a garland of flowers bursts apart into a ring of porpoises. Beads of foam act as a kind of prism. It can’t be undone but it is being undone right now. The floor of time drops down, releasing a cloud of sand, and from out of the shipwreck, tragic but below us, harmony reconstitutes itself.

Tomorrow I would be walking up that hill again, soon, because a throw of the dice will never abolish chance.